DOI: 10.18441/ibam.24.2024.86.79-101

Pablo Turnes

Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina

pturnes@sociales.uba.ar

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8163-1992

The four works that have been chosen, while being quite different in tone and style, can be said to share a number of characteristics which can be considered in the context of Argentine history and Argentine comics traditions. The first and most obvious of said characteristics is the way these comics can be regarded as sci-fi stories. To be more specific, all of these stories are presented –in a more or less explicit way– within a dystopian frame. Argentine philosopher and sci-fi essayist Pablo Capanna had already pointed out in his seminal work The meaning of Science Fiction (1966), that dystopia had increasingly become the exclusive sub-genre within sci-fi literary production in both the US and England. In the first decades of the 21st century, this sub-genre has become mainstream. For countries like Argentina, where economic, political, and social crises have become a recurring historical status, dystopia has transformed from being a way to imagine a distant future to serving increasingly as a political commentary on the current state of affairs.

Dystopian works as a generalized symptom in Western culture during the second half of the 20th Century can be defined as a loss of faith in the future, that is, the future tends to be perceived as something progressively worse than the past and as something more oppressive, even when technologically more advanced. Sometimes, there is no future at all, just the remnants of what was once human civilization. It can be considered the reverse of positivist dreams, hopes and longings based on the idea that scientific techniques would lead to a better world; a rational utopia made possible by technological advances and discoveries.

This article aims to track how this scenario plays out within an Argentine context. This is closely related to the way South American elites of the 19th Century embraced positivism as a way to, on the one hand, follow their European role-models of development –England and France mainly– and on the other hand, to profit from this accelerated progress which would lead these new nations to jump ahead, becoming developed countries in a much shorter time-span than their European counterparts. Coincidently, the first texts that can be identified as belonging to the utopian/sci-fi genres were not only produced during the second half of the 19th century, but were written by authors who were involved in their countries’ political processes. As Haywood Ferreira has accurately pointed out:

From the nineteenth century to the present day, science fiction has consistently proved to be an ideal vehicle for registering tensions related to the defining of national identity and the modernization process. These tensions have long been exacerbated in Latin America by the challenge of constructing and/or maintaining a national identity in the face of significant influence from the North and by the uneven assimilation of technology in Latin American countries (Haywood Ferreira 2011, 5).

Frederick Jameson has pointed out a key element about utopias and their constitutive contradictions; Thomas More’s Utopia starts with the digging of a trench to turn that piece of land into an island, separating the new country from the rest of the world to accomplish its utopian goal: a “radical secession” (Jameson 2005, 5). We can think of other examples, from Francis Bacon’s De Atlantis (1627) to Robert Nozick’s Anarchy, State and Utopia (1974). In this tradition, we could add Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (1811-1888): intellectual, military leader, writer and president of the Argentine Republic between 1868 and 1874. In 1845, he published Facundo o Civilización y barbarie. In his biography of federalist caudillo Facundo Quiroga (1788-1835), Sarmiento opposed the barbaric country to the civilized city. This work would define an ideological binary that would become deeply rooted in Argentine state politics, as in Argentine culture. Five years later, in 1850, Sarmiento would publish what can be considered a utopian text: Argirópolis [meaning the City of the River Plate].

Sarmiento’s goal was to avoid further division between the new South American republics by creating a new capital that would act as a gathering point to some of the former Spanish territories but which, at the same time, would keep its distance from the continent. Thus, in classical utopian fashion, he chose an island: Martin García Island, in the River Plate. Moreover, the accomplishment of Argirópolis was closely tied to architecture, the material foundation for the utopian project. This is something Jameson has also pointed out: utopias tend to favor design and architecture before the other arts, something made manifest, for example, in William Morris’ work (Jameson 2005, 152).

The unifying utopian project, however, did not include the “savage territories”, which at that time meant the Patagonia. These territories were considered, in Hegelian terms, beyond the boundaries of History. European immigration would be given the task to “civilize” the barbaric lands and their native occupants, one way or another. Despite Sarmiento’s proposal never coming to concretion, this territorial logic based on a limit between civilization and barbarism would become Argentina’s ideological foundation. Even after the extermination of the Patagonian natives and the consolidation of the State’s control over those formerly savage lands, this logic did not just fade away.2 The city of Buenos Aires would become the cosmopolitan center of the newly founded republic, where economy, culture, and politics would be and still are owned mainly by the city; meanwhile the rest of the country (the interior, the deep country) would remain –from this perspective– more closely tied to the old colonial customs, underdeveloped, superstitious and violent.

Furthermore, this logic has been reinforced from the second half of the 20th century onwards, by a division between the province of Buenos Aires and the city of Buenos Aires. General Paz Avenue –the limit linking the province and the city– has become a new frontier between civilization and barbarism. That which is beyond those limits is shown by media and rooted in the social imaginary as a lawless place, where crime, poverty and decadence turn the inhabitants of the province to second-class citizens, subhuman subjects beyond redemption.

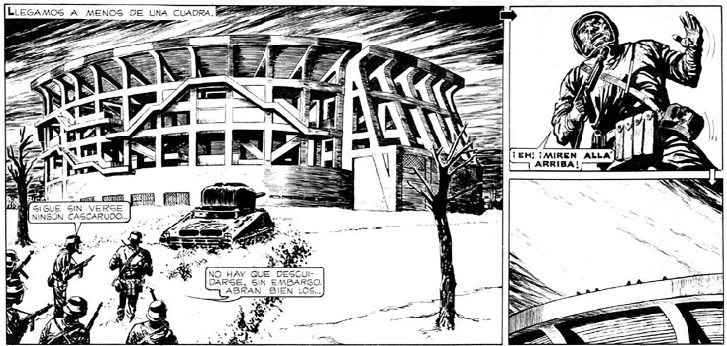

There is an unavoidable figure when it comes to the subject of sci-fi and utopia in Argentina: Héctor Germán Oesterheld and his seminal work, El Eternauta (The Eternaut, originally published between 1957 and 1959, with art by Francisco Solano López), the story of a worldwide alien invasion shown through the eyes of a small group of Argentine friends and neighbors (Fig. 1). The original impact of this story among readers was based on the fact that it happened in recognizable places between the province and the city of Buenos Aires.3 Until then, the Argentine adventure comics genre took place in decontextualized scenarios: jungles, the outer space, and the far west. Argentine daily life was not deemed as a plausible context in which any adventure might occur, hence El Eternauta’s originality. Joanna Page has defined it as a “materialist framework for understanding human evolution and class struggle” (Page 2016, 48). But there is yet another work by Héctor Oesterheld to bring forward: La Guerra de los Antartes (The War of the Antartes).

This comic had two versions (the first having been published in 1970, with art by León Napo), of which the second came to be the best known (with art by Gustavo Trigo). Published in Noticias magazine between February and August 1974, the story depicted, once again, an alien invasion shown through Argentine eyes, with Buenos Aires as one of the local scenarios where the action took place. This might be the only and probably last example of a political utopian sci-fi comic in Argentina. Oesterheld was at that time engaged with Montoneros, a revolutionary Peronist organization. WoA was left unfinished since Noticias magazine was tied to the organization and it was declared illegal by the government in 1974. However Oesterheld left enough clues to let readers understand the differences between The Eternaut and WoA: while the first was meant to be read as something that was happening within a contemporary daily context, the latter was placed in a futuristic setting where revolution had already succeeded, where the Montoneros utopia was a tangible reality. There was no leader but “counselors” who spoke to the people in Plaza de Mayo from the balconies of the Casa Rosada, the presidential palace, a clear reminiscence of Peronism’s classical political liturgy (Fig. 2).

The change from a presidential power to an assembleary model was significant in that context: it meant Perón’s figure had been replaced by the organization and that a leader was no longer necessary. Perón died while this comic was being published, and a month later the magazine and Montoneros were declared illegal and the organization went underground. From then on, dystopian sci-fi would become a significant trend in Argentine comics as a way to metaphorize the oppression of daily life under military rule.4 Even after the end of the dictatorship, in 1983, this approach to sci-fi comics would continue to prove popular among readers to the point that it would become a cliché. This was also related to the major influence European sci-fi exerted on Argentine comics, through the work of authors such as Enki Bilal and Moebius [Jean Giraud] and magazines such as Metal Hurlant and El Víbora, which inspired Fierro magazine.

In brief, after 1976 –the year the last coup began– the idea of Argentina as a developing country was permanently shattered. From then on, neoliberal policies would scrap what was left of the local industry, the source of yesteryear’s national pride.5 The 2001 economic crisis would threaten to return the country to a pre-national state, devolving centralized power and social identities to more local, provincial organizations. The turn of the century would find Argentina living its own self-prophesized dystopia.

The crisis would also have a great impact in comics’ production; the end of the industrial era, with all the big publishing companies bankrupting one after the other, left artists with no choice but to start producing their own comics, whether that meant a fanzine or a magazine resembling the classic model of periodical publications. However, it was the Internet and blogs that allowed artists to start showing and sharing their comics, something that would eventually be redirected towards social networks.

A key actor during the early years of the 21st century was comics writer and artist Diego Agrimbau (Buenos Aires, 1975), who was part of the foundational comics blog Historietas Reales in 2004, and who –like most of the artists whose works will be analyzed here– was part of a generation of comic artists who had to transition from the 1990s comics scene (marked by the collapse of the industry, self-publishing and comics-for-export production as survival strategies) to that of post-industrial Argentina, which gave place to new kinds of narratives and formats. Agrimbau’s work can be also interpreted as the continuation of an Argentine sci-fi comics writing tradition, starting with Oesterheld, and following with Carlos Trillo (1943-2011) and Ricardo Barreiro (1949-1999). He earned renown with his work La Burbuja de Bertold (with art by Gabriel Ippóliti), published in France in 2005 by Albin Michel (La Bulle de Berthold), described by King and Page as a “technodystopia” (2017, 21).

While Agrimbau’s take on the genre cannot be overlooked, it’s hard to ascertain how much of an influence –if any– he has exerted on the works examined here. First of all, he is part of the same generation of artists6, yet with a stronger formalist approach to comics. And second, he has a strong and evident link to French sci-fi comics from the 1970s and 1980s, which can also be found in Ippóliti’s style, close to that of Enki Bilal (1951) and the “classic” European canon. This is hardly the case with the rest of the artists, which differ greatly from technodystopian aesthetics, distancing themselves from the European cannon and proposing more of a sui generis approach.7

Another important milestone would be the re-launch of Fierro magazine in 2006, the only periodical –monthly in this case– nationwide comics magazine. As a matter of fact, three of the four works chosen for this article were first serialized in Fierro before being published as graphic novels.8

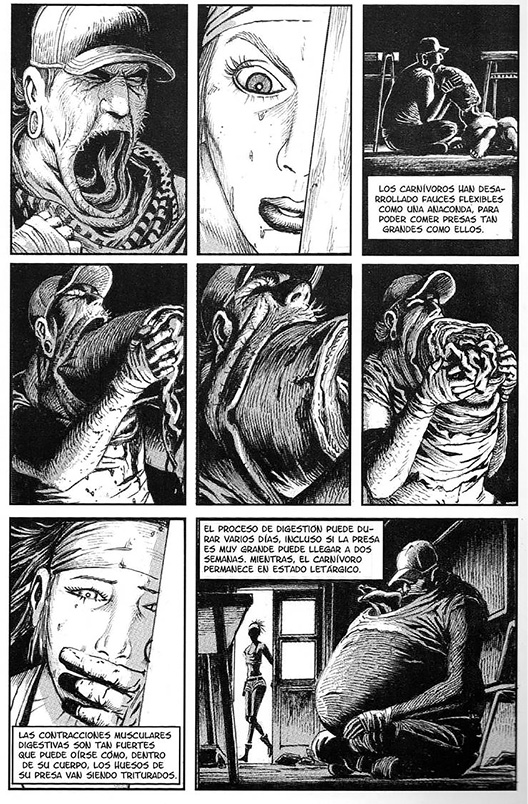

Our approach takes an inverted path from that followed by El Eternauta; it starts in the city of Buenos Aires and then it progressively moves farther away from the capital and into unknown territory. The first case is El Esqueleto (The Skeleton), by Salvador Sanz.9 The story takes place in the near future in contemporary Buenos Aires. An unknown virus has infected cattle, which ends up infecting humans and turning them into meat-addicts. These meat-eaters evolve into a new species, becoming able to swallow and digest entire preys, both human and non-human (Fig. 3). The only way to avoid turning into a mutant is to become a vegetarian. Mandatory veganism can be considered dystopian in itself to such a strong meat-eating culture like Argentina’s.

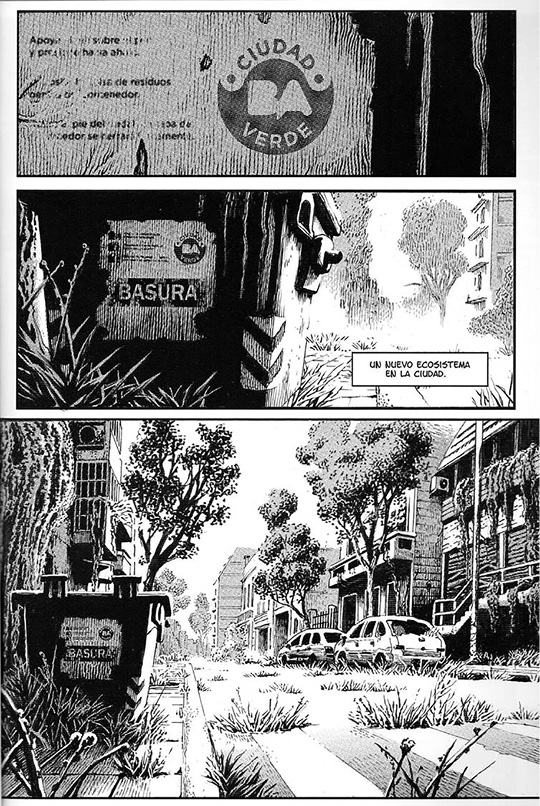

While Sanz is never politically explicit, the use of irony can be interpreted as criticism against Buenos Aire’s isolation, a city governed by neoliberal political cynicism. The trash bins with the “BA Ciudad Verde” (BA Green City) logo actually exist, but in reality this is more related to political marketing rather than actual recycling politics, which are basically non-existent in Argentina and have never been seriously developed by any government (Fig. 4). This weighs heavily in the overall ideological tone of El Esqueleto, which ends up proposing the need to restore some kind of natural balance, the creation of a society that is neither carnivorous nor herbivorous but something else. The scenes of meat-eating mutants chasing groups of vegetarian survivors can also be considered a bitter look on the aggressiveness of daily life in Buenos Aires.

El Esqueleto is closer to El Eternauta tradition in the way that it sets the action in recognizable places such as the Natural Sciences Museum and the National Library, depicted in a realistic style. These places are not mere scenery; they are also symbols of that which is rendered useless by the involution of society. The remnants of the past are nothing but ruins of that which was once called “culture”, the failed promise of knowledge as the key to progress.

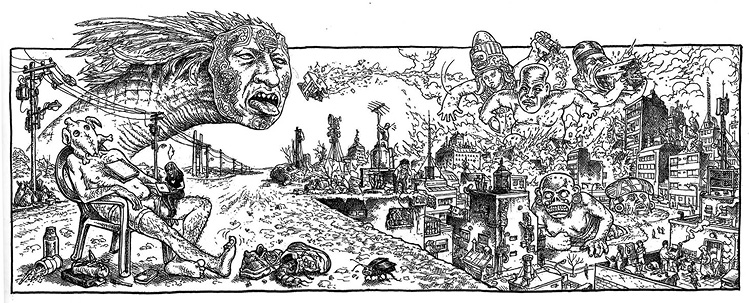

Following the aforementioned reverse path, the second story goes beyond the limits of the civilized city and into the capital’s conurbation –commonly known as Conurbano– such as it is presented in Frank Vega’s work, a comic artist who lives in the always dreaded realm of the Greater Buenos Aires. Vega has been defined as a post-industrial artist, and his comics and drawings can be considered sci-fi the way William Burroughs’ literary work sometimes is: places and people are presented as alienish mutants; everything is alive in a monstrous way; grotesque creatures and characters coexist with seemingly normal human neighbors. Vega’s surreal world is one where the Apocalypse has already happened: unemployment, pollution, a life where the boundaries between what is legal and what is not are sketchy, with shady everyday characters only found in that forgotten piece of the world (Fig. 5).

This is a territory permanently transformed and deformed by power: politics, media, the police, local drug dealers, rock-and-roll loving slackers, people trying to constantly adapt and survive in a harsh environment. Vega shows us the Conurbano’s typical features: the streets; the houses with their water tanks placed on the roof; the walls covered with graffiti; political propaganda sporting the faces of local politicians; abandoned factories; bleak, chaotic, dirty downtowns. Yet Vega is not morally judging his own reality but rather embracing it as his identity, an acceptance that there is also freedom in chaos.10

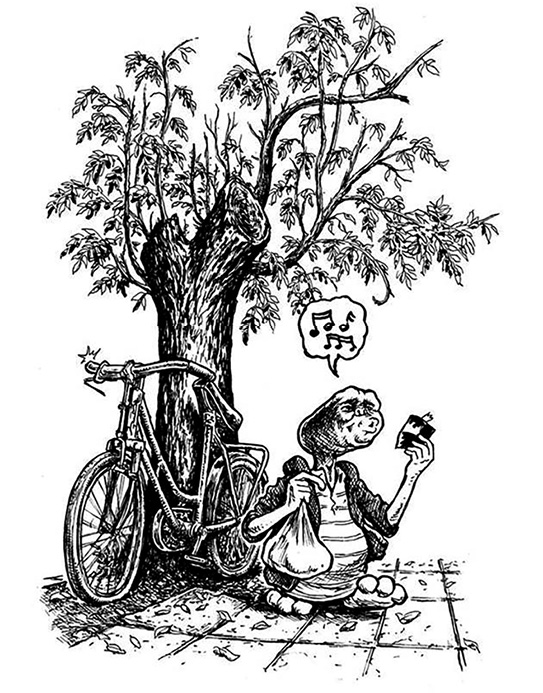

Vega also superposes cultural references, from Arthur Schopenhauer to Mesoamerican deities; Igor Stravinsky shares space with cumbia idols; Louis-Ferdinand Céline; Kurt Cobain; and Star Wars characters. This grotesque, kitsch world Vega invents for himself is filled with nods to pop culture. The best example of this is his most recurring character, Pititi (Fig. 6). It is evidently an homage to Spielberg’s E.T. the extra-terrestrial, but also to E.T.’s bizarre 1980s Argentine rip-off, Monguito –a derogatory word meaning “the little retard”–.

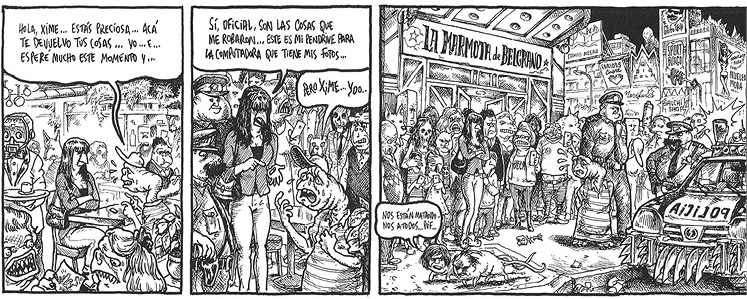

Pititi serves as a metaphor for the alienated middle-class suburban youngster who lives with his parents, hangs around with the local gang, and occasionally earns some money working as a delivery boy, the kind of generalized precarious work that is common to post-industrial economies. Pititi’s alienness is reinforced by the way he is looked down on when he goes to the big town, Buenos Aires. In the character’s longest story so far, he buys a stolen cell phone that comes with a pen drive in which he finds pictures and the CV of the owner, a beautiful girl who lives in the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires. Vega mischievously changes the name of the city from “autonomous” (autónoma) to “automaton” (autómata). Pititi fantasizes an encounter under the excuse of giving the girl back her stuff, which he does, but it turns out to be a setup; the girl had already called the police, who were waiting for the boy from the Conurbano to arrest him (Fig. 7). He’s an alien, and to the eyes of the inhabitants of the capital, he cannot be but a thief, a petty criminal, the receptacle of classist hatred. Edward King has noted the following:

These science fiction tropes function both as a way of representing power shifts from authoritarian state power to market-driven neoliberal power, and as a device with which to suspend representation and give expression to affective connections, the possibilities of which become visible in the interstices of this shift (King 2013, 5).

Following King, Vega’s work can be seen as a radical distortion of costumbrismo. Under neoliberal rule, reality shifts in an increasingly accelerated pace; thus, realistic and naturalistic representational strategies risk becoming reactionary as well as quickly outdated. Under this light, Mortadelas Salvajes can be understood as a way to translate, rather than to just “represent”, the way the commodification of life spawns a mutated reality, closer to body horror than to documentarism.

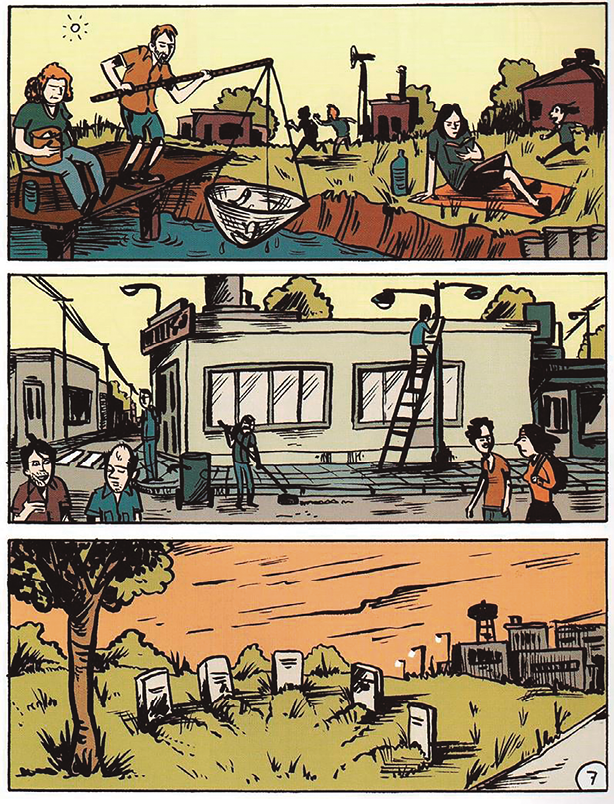

Our third case takes us even farther away from urban centers, but keeps the story within the rural boundaries of the province of Buenos Aires. Federico Reggiani and Ángel Mosquito’s Tristeza (Sadness) shares a common trope with El Esqueleto: an unknown virus transmitted by cows causes the destruction of society.11 The sickness is known as “the sadness”, a kind of extreme depression that makes people give up their will to live (Fig. 8). The story is divided into two parts. The first part shows a group of people fleeing the urban environment and heading for the country. They have to learn to survive, to hunt, to gather food and water, to help a woman give birth with no professional aid, to educate their children. Though it all seems to work at first, they find a group of kids who have turned into savages living nearby. Coexistence becomes impossible and dangerous, so the group decides to flee once more.

The second part of the story finds the group discovering an urban settlement that has become organized, defining itself as a place that, according to a local guard, is “like the world before, but improved”. Among other things, they generate electricity, have enough food supply for everybody, and there is no private property. There is also a strict social organization divided by tasks, a technocratic order headed by a mysterious leader. The visible face of this new order is known as The Engineer. Their motto is “Peace and Progress”, a mixture of South American positivist mottos.12 Furthermore, the dining room where everybody gathers to eat is named after Domingo Faustino Sarmiento. In brief, this new utopian society is the consecration of the dreams of the founding fathers: a social order halfway between rural collectivism and urban development (Fig. 9). Felipe Gómez has summed it up correctly:

Trying to preserve a sense of “civilization” while battling “barbarity”, these characters shy away from immutable or invariable nation-based, and even linguistic, models in order to reconfigure scientific and technological knowledge. They employ material, cultural, and spiritual remains and debris as available resources, and shuffle the composition of social groups to adapt, resist, and rewrite the conditions imposed by external threats […] (Gómez 2021, 221).

Things do not last for long, though. There is resistance to order, expressed as a kind of cult that worships “La Santita”, the little saint, based on an actual cumbia singer who died tragically in the 1990s, known as Gilda [Miriam Alejandra Bianchi, 1961-1996]. Gilda has been unofficially sanctified in Argentina, a popular, almost heathen figure, something not uncommon in Latin American countries, where catholic customs are mixed with pre-Columbian and African cults. La Santita is also reminiscent of yet another popular sanctified figure: Eva Perón. So, Positivism and popular beliefs –or even populism– manifest themselves as antagonistic forces, something intrinsic to Argentine society and as such, unavoidable: civilization and barbarism are not mutually exclusive, but rather intertwined factors within an unsolvable equation.

In the end, an uprising takes place and the popular forces take control. The Engineer is killed and the leader is shown as nothing but a weak man, whose only reason to stay out of the public eye was living in a permanent state of debauchery with girls, alcohol and drugs. When the tide turns, he quickly adapts to change and shows himself as someone totally devoted to La Santita. Part of the group stays in the newly formed urban society; the rest decides to leave and return to the country, looking for a better, freer way of life despite its precariousness. Life goes on one way or another, and the dead are buried. (Fig. 10) In a country with a long tradition of political violence, where “disappearance” is still a sinister reminder of the recent past, such civilized gesture lays the promise of a better world, despite the authors’ political skepticism and pessimism.

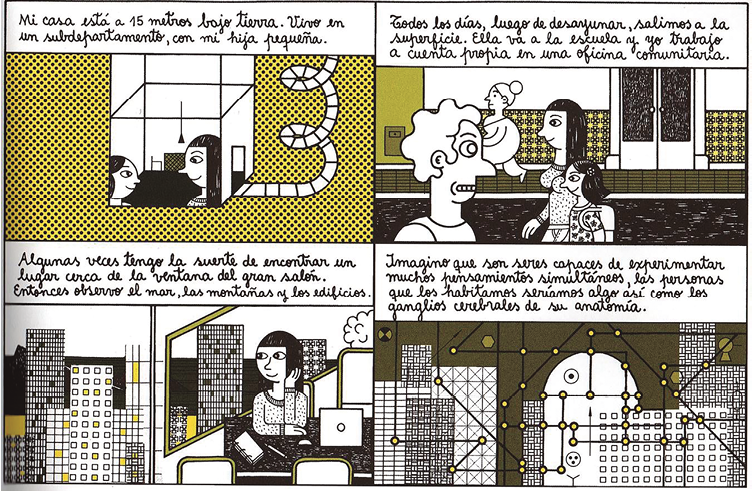

Lastly, we have Delius’ short story–“Lunatmósfera”, included in Las ciudades que somos (The cities we are), a graphic novel by comic artists collective Chicks on Comics. This is the only story of the four that was not originally published in Fierro magazine, since it was produced exclusively for the graphic novel format. Delius sets the story in a futuristic Rio de Janeiro, where she and her daughter live in an underground apartment, fifteen meters below the surface. The narrative is shared between the mother and the daughter, each describing their reality with their own voices. The city is shown as a technological utopia, where hyper-modern skyscrapers and towers coexist with the sea and the mountains. People live and work on the surface by day, going back to their underground homes at night (Fig. 11).

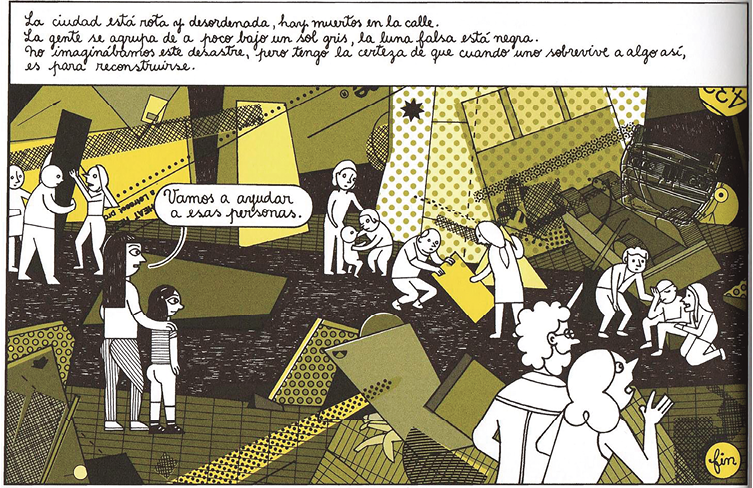

We can see there is excitement in the city’s air; arrangements are being made for a big, worldwide celebration. The reason is the launching of a new system consisting of four magnetic spheres –which Delius describes as “artificial moons”– that will allow the government to control weather. Despite all of the technical preparations, something goes wrong and disaster ensues. The next day, mother and daughter go back to the surface and witness the chaos left by the failed experiment. However, their last words are not of fear and disappointment, but of hope: “The city is trashed and messy, there are dead on the streets. People slowly gather together under a grey sun; the fake moon is black. We did not imagine such a disaster, but I am certain that when one survives something like this, it is to rebuild”.

The final page shows mother and daughter getting ready to face the future, which lies beyond the panel, a still undefined narrative. “Let’s go help those people”, says the mother (Fig. 12). This encouraging open end differs from most sci-fi narratives (including those analyzed in this text). Kurlat Ares, in her analysis of Diego Agrimbau’s and Gabriel Ippólitti’s work, has defined the 21st century Argentine sci-fi comics by stating that “[t]hese are comics marked by enormous pessimism and whose ideological readings restore the experience of political anomie”.13 Delius seems to defy this pessimistic approach to the genre not by denying its inception based on a civilizational crisis, but rather proposing the reconstruction of social ties through solidarity. Such an act in the midst of apocalypse cannot be but a kind of political engagement, a way to redefine the social contract.

These four comic works were published between 2011 and 2018, that is to say during this last decade. Why this persistence of science fiction as a way to speak about the present? And what kind of present is that which drives us to make use of such oblique narratives to speak about it? It looks like the future not only seems unimaginable, but undesirable: the possibility of a global ecological catastrophe in the short-term, the growing number of species facing extinction, melting ice caps, agrotoxics, greenhouse effect, the risk of nuclear war, oil spills, deforestation, refugees, displaced people, and so on and so forth.

It seems as if Apocalypse was happening all the time, to the point it is naturalized by becoming integrated into daily life. The increasing dependency on technology reveals that the technological utopia is not an emancipatory one; it translates into an addictive, fearful dependency which in turn creates feeble, atomized societies. Narratives such as the ones analyzed throughout this article show us that, while not being able per se to change reality, they are still needed as an imaginative strategy to approach current issues in the public agenda. Concurrently, sci-fi in Argentina –as in other Latin American countries– has always been tied to its immediate political, social and cultural context:

It is certainly the case that Argentine science fiction, while engaging with themes common to the genre across the industrialized world –from the abuse of technology by authoritarian regimes to new modes of posthuman subjectivity and apocalyptic visions of environmental catastrophe– is also thoroughly grounded in the specific social and political life of the nation (Page 2016, 5).

Considering these factors, it is not hard to see why sci-fi is persistent. If we follow Frederick Jameson’s famous assertion that “it is easier to imagine the end of the earth than the end of capitalism”, we find the ideological core of what Mark Fisher has called “capitalist realism”.14 That is to say, an idea tightly inscribed within contemporary common sense that installs an apodictic principle: there is no real alternative to the capitalist system; any other possibility is disregarded as folly.

Paradoxically enough, sci-fi is a consequence of the industrial era - and so are comics for that matter. There lies its potency: it is a genre that speaks from the very heart of the system. It is there to warn, to provide tools of reflection, to entertain and disturb at the same time. Sci-fi in Argentine comics is a long-standing tradition and it has been –at least for the last four decades– a political genre. Tracking the changes in the way sci-fi acknowledges real issues means to treat these works as testimonies of a given historical period. Capanna proposed interpreting sci-fi as a philosophy (Capanna 1966, 48), and its relation to myth: “[…] it’s a myth, but a myth built in a platonic sense, which has taken the shape of mass literature due to historical demands”.15 This relationship between sci-fi, philosophy, myth and Apocalypse is also something Danowsky and Viveiros de Castro have pointed out:

The “end of the world” is one of those famous types of problems of which Kant used to say human reason cannot solve, but cannot help posing at the same time either; and it does so necessarily in the form of mythical fabulation or […] of “narratives” that orient and motivate us (Danowsky and Viveiros 2017, 6).

If we consider these works from this perspective, a first observation should outline that all of these artists started their career in comics during the 1990s. They were the first post-industrial generation of Argentine comic artists and it was during the first two decades of the 21st Century that they established a reputation in what can be considered a “consecrated” career. That is to say, they have published several works; they have gained renown in the Argentine comic circuit; in some cases, their works have been published abroad; they possess a fan base and they continue to develop their careers. So, their “return” to the sci-fi genre is far from being a fashionable move. Having in mind that the breakdown of the local comics industry in the 1990s caused later generations of readers to ignore that which had been produced in their own country, this revisitation of the sci-fi genre seems like an attempt to reclaim the connection with the previous generation of comics artists and tropes.

Within this new context –the 21st Century that is– dystopian sci-fi comics have regained some kind of political agenda. As expected, that agenda has changed since the 1980s, but it is the genre itself that allows, and even demands, artists to take a stand by facing immediate issues. Edward King and Joanna Page argue that

[…] while the graphic novel in Europe and North America is currently dominated by autobiographical and journalistic textual modes, the most prevalent genre in Latin America is science fiction, making the region a highly fruitful one for an exploration of the posthuman in the contemporary graphic novel (King and Page 2017, 2).

As arguable as the “domination” of the sci-fi genre in the Argentine comic medium might be, Argentine comics have indeed kept –up to a point– a close tie to “classic” genres, which have gone through several redefinitions in connection to their production context in the early 21st century.16

Two of these stories (El Esqueleto and Tristeza) are built around the idea of everyday food becoming the cause of Apocalypse, the very economic model provoking social collapse. It’s not hard to see a warning there, the need for some kind of restoration of balance. Argentina’s primary economy’s technification has meant the depopulation of the countryside, in favor of efficiency and productivity. Yet, at the same time, the consequences of these changes can be seen in the way small provincial towns have been and continue to be, affected: incredibly high cancer rates, malformations in newborns, child exploitation, etc.; all of which is absent both in politics and in the mainstream media.17

Another issue present in the stories is the city versus the country. The city, formerly taken as a synonym of civilized life, has turned instead into a hostile place to live. This had already been experienced by the very political elite which had declared war on barbarism, planning in turn to repopulate Argentina with European immigration during the late 19th century. Despite the Argentine elite’s plans, immigrants came mostly from Italy and Spain, far from the Nordic inhabitants Sarmiento had in mind. If we add radical political traditions like anarchism and communism, which were unknown in Argentina until then, it is easier to understand why the elite reacted by reconstructing for themselves an idealized, bucolic image of the country; a space devoid of social unrest and political conflicts.18 This is common to countries that have experienced fast-growing urban spaces: an increasing nostalgia for the quiet, peaceful life of old. In Argentina, this is reinforced by the fact that Buenos Aires is the city, the result of a highly centralized political and economic system. Kurlat Ares has pointed out that

The cities that had been the driving force behind the projects of the future modernity of the nineteenth century become in these comics a corrupt and corrupting space, where the norms of civility and empathy can barely exist in very limited community spheres. Social ethics have disappeared to be replaced by the limited possibilities of individual options of dubious scope and short term. The ideal subjects that had been at the center of the nineteenth-century discourse on the desired nation, in the comics, capitulate or resist without hope, but they are not the idealized subjects of the populist discourse that prevails in other areas of the literate field.19

We have seen Vega’s approach to this subject, the grotesque depiction of life in the boundary between the city and the country; between civilization and barbarism. A growing urban tissue destined to become integrated to the capital that feeds on it; yet at the same time that tissue is hypocritically rejected by the big city, as if it was a virus, something infectious. The return to the country, however, is also demystified: Tristeza, which sets the actions in the opposite side of the spectrum than that of El Esqueleto, does not translate as the need to embrace some kind of neo-ruralism. On the contrary, it shows how the utopian collectivism based on small communities of farmers and knowledge can only function by rejecting the “irrational” part present in every large social group.

The totalitarian temptation seems to shadow the technocratic experience posed in terms of emancipation through technification. This danger is strengthened by the reemergence of tribal communities within the larger community: an absolutely rational society becomes a repressive one when it denies itself the possibility of other ways to experience life in common. Within a Latin American context, this can be also understood as the paradox posed by post-colonial societies: the denial of the preexisting traditions and customs performed by the new Nation States which aim to reach a “developed” status by leaving behind a past deemed as the cause of all of the country’s setbacks.

However, Delius’ short story does not give up the idea of the city as a livable place; she presents urban life as the only way to generate true change, even if that means destruction as the price to pay. The Latin American city becomes, once again, the epicenter of a historical shift. Furthermore, King and Page have maintained that “[…] such narratives tend towards a dystopian –and ultimately, thoroughly humanist– vision, registering a nostalgia for a human uniqueness that is under threat and destined to disappear” (King and Page 2017, 4). While their warning of a reactionary reification of a Cartesian definition of “humanity” through sci-fi is an argument to be mindful of, not all of sci-fi can be reduced to sub-genres such as steampunk and cyberpunk (which, to be fair, is the main point of interest in their work).20 On the other hand, their assertion that many of these works can be understood as an “anti-capitalist critique in the rioplatense region of Latin America” (King and Page 2017, 43), is indeed a good observation that can be applied to the comics explored in this article.21

Thus, the last story turns the tables by taking something that is dystopian in principle and turning it into a utopian proposition, though not from a naïve position but from an urgent need in a hostile context. In this sense, Delius’ story would seem to break with the aporia presented by the other three stories: the acceptance of the end is not just about surviving –whether this means to leave the city behind or live in what’s left of it, or in the nether realm between frontiers– but rather to accept it as part of a larger and non-linear process of social construction and re-construction.

Despite traits such as cynicism, skepticism and pessimism that tend to be underlined when dealing with the dystopian sci-fi genre, one characteristic does unite all of the works: the end is always open-ended. Stories about the future cannot, by logic, predict those futures’ hereafter. The fact that dystopian stories always leave readers a vanishing point to wonder what an after-future could be like seems to contest Jameson’s formula by stating that the end of capitalism is being imagined all the time; the world seems to endure end after end, none of which so far has proven to be the definitive one. After all, to quote Danowski and Viveiros de Castro (2017, 35), the end is the world’s mode of existence.

Capanna, Pablo. 1966. El sentido de la ciencia-ficción. Buenos Aires: Columba.

Danowski, Déborah and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro. 2017. The Ends of the World. Translated by Rodrigo Nunes. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Delius. 2018. “Lunatmósfera”. In Las ciudades que somos by Chicks on Comics, 13-24. Madrid: Sexto Piso.

Fisher, Mark. 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is there no Alternative? Winchester: Zero Books.

Gómez, Felipe. 2021. “Will it be Possible? Apocalypse and Resistance in Latin American Graphic Novels”. Paradoxa 32: 201-24.

Haywood Ferreira, Rachel. 2011. The Emergence of Latin American Science Fiction. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Jameson, Fredric. 2005. Archeologies of the Future. The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions. New York: Verso.

King, Edward. 2013. Science Fiction and Digital Technologies in Argentine and Brazilian Culture. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

King, Edward, and Joanna Page. 2017. Posthumanism and the Graphic Novel in Latin America. London: UCL Press.

Kurlat Ares, Silvia. 2015. “Los futuros posindustriales de la historieta en la era del populismo. El caso argentino”. Iberoamericana 15, n.o 57: 131–44.

Oesterheld, Héctor y Francisco Solano López. 2012. El Eternauta. Buenos Aires: Doedytores.

Osterheld, Héctos y Gustavo Trigo. 1998. La Guerra de los Antartes. Buenos Aires: Colihue.

Page, Joanna. 2016. Science Fiction in Argentina. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Reggiani, Federico, and Ángel Mosquito. 2014. Tristeza. Córdoba: Llanto de Mudo.

Sanz, Salvador. 2016. El Esqueleto. Buenos Aires: Ovni Press.

— 2017. El Esqueleto: el fin de todas las especies. Buenos Aires: Ovni Press.

Vega, Frank. 2014. Mortadelas Salvajes. Buenos Aires: Tren en Movimiento.

Manuscript received: 11.10.2022

Revised manuscript: 28.06.2023

Manuscript accepted: 22.05.2023

1 This article was originally presented in the Comics and the Latin American City conference, University of Manchester, June 25th-26th 2019.

2 The southern Patagonian regions were occupied and taken by force manu militari in what is commonly known as Campaña del Desierto (Desert Campaign), between 1878 and 1884. The Argentine State’s strategy consisted of moving troops into native territory (inhabited by Mapuches, Tehuelches and Ranqueles), destroying their settlements, killing, and capturing survivors, many of which ended up as servants for the Argentine upper classes. Official reports established the number of natives killed and/or taken prisoners around 14,000.

3 Héctor Germán Oesterheld (1919-1978?) is the most renowned writer of comics in Argentina. In 1957, along his brother Jorge, he founded Editorial Frontera, the publishing house that would modernize and change the way of making comics in Argentina from then on. Along with artists such as Hugo Pratt, Alberto Breccia and Francisco Solano López (among many others), he would conceive series now considered classics of the comics medium e.g., Sargento Kirk, Ticonderoga, Ernie Pike, El Eternauta, Mort Cinder. In the early 1970s he joined a left-wing Peronist revolutionary group, Montoneros. His commitment to this organization would put him on the black list of the military dictatorship that took over Argentina between 1976 and 1983. In 1977 he was kidnapped by the Army and was never seen again. It is believed he was executed somewhere near Mercedes, in the Province of Buenos Aires, in 1978. He’s one of the thousands of Argentinians that remain desaparecidos.

4 The second part of El Eternauta, published between 1976 and 1978 (Oesterheld had already completed the script before being kidnapped), can be seen as the end of the utopia and the acceptance of revolutionary sacrifice in the face of defeat. From a different perspective, Page has noted about this second part: “El Eternauta II can be seen to enact the increasing proximity of the intellectual to the masses he or she was previously seen as ‘representing’ from afar” (Page 2016, 37).

5 While attempts of free-market economic reforms had taken place after the 1955 coup against Juan Domingo Perón, it was with José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz, Minister of Economics between 1976 and 1981, when neoliberal reforms finally took root. Based on Milton Friedman’s monetarist principles, Martínez de Hoz ensured that his reforms would endure through successive technocratic agents during democratic times. It was under Domingo Felipe Cavallo’s role as Minister of Economics (1991-1996; 2001) that neoliberal policies were applied in full. During Fernando de la Rúa’s term (1999-2001), Argentina entered the 21st century heavily indebted, with the highest unemployment rate in its history (25% of the population) and a deep economic recession. A popular uprising would force President De la Rúa to resign in the last days of December 2001, two years after he had taken charge. Argentina’s economy would eventually grow again, but it would never recover its pre-1976 economic indicators.

6 Diego Agrimbau was born in Buenos Aires in 1975; Delius (María Delia Lozupone), was born in in 1974 in Buenos Aires; Ángel Mosquito was born in Martínez (Province of Buenos Aires), in 1976; Federico Reggiani was born in La Plata in 1969; Salvador Sanz was born in Buenos Aires in 1975; Francisco [Frank] Vega was born in Buenos Aires in 1974.

7 This is not the same as saying that Agrimbau’s work lacks originality. Far from it, his works deserve a more in-depth, overall approach. For an scholarly approach to his work, see the texts by King and Page (2017) and Kurat Arles (2015).

8 Fierro’s first run took place between 1984 and 1992, published by Ediciones de la Urraca. Between 2006 and 2019 it was published as a Página 12 newspaper supplement.

9 El Esqueleto was originally published in Fierro magazine between 2015 and 2017. Ovni Press compiled it in two volumes: El Esqueleto (2016) and El Esqueleto: el fin de todas las especies (2017).

10 Vega’s short comic strips were published for the first time in Fierro magazine in 2012 and compiled in 2014 by Tren en Movimiento.

11 The story was originally published in Fierro magazine between 2011 and 2012. In 2014 it was compiled and published by Llanto de Mudo.

12 More specifically, it refers to Brazil’s motto Ordem e Progresso (Order and Progress), and to the Argentine motto in times of Julio Argentino Roca’s first government (1880-1886): Paz y Administración (Peace and Administration).

13 Original: “Se trata de historietas marcadas por un enorme pesimismo y cuyas lecturas ideológicas reponen la experiencia de la anomia política” (Kurlat Ares 2015, 136; English translation by Pablo Turnes).

14 The concept “capitalist realism” is based on that very phrase attributed to both Frederic Jameson and Slavoj Žižek. Fisher defines it as “the widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it” (Fisher 2009, 2).

15 Original: “[…] es mito, pero mito construido a la manera platónica, que ha tomado la forma de una literatura de masas por exigencias históricas” (Capanna 1966, 215; English translation by Pablo Turnes).

16 In this article, the hypothesis about the sci-fi genre is less about its dominance than its persistence, as well as its historical relationship with other sci-fi works during periods where these narratives have had a particular political meaning. With respect to King’s and Page’s statement, I argue that the autobiographical turn in comics –whose birth can be traced to the mid-1960s and the early 1970s in the USA– had some early manifestations in Argentina at the beginning of the 21st century that would mark an increasing production of such genre up until today. The blog Historietas Reales, started towards the end of 2004, meant a significative detour from the more classic genres that comics in Argentina have had until the collapse of the industry in the eve of the 2001-2002 crisis. As a matter of fact, the most renown Argentine sci-fi comic writer from the 21st century, Diego Agrimbau, would be one of the founders of said blog. His early comics, and later his work with artist Dante Ginevra (El Asco), was very different from his sci-fi work which was first published in France and only afterwards in Argentina.

17 Argentina is maybe the country that makes the most extreme and generalized use of agrotoxics in the world, glyphosate in particular. The issue is far from being present in the public agenda, and yet it means a great risk for the health of Argentine population. Glyphosate (C3H8NO5P) exists in various commercial versions, Monsanto’s Round Up being one of the most used. Though institutions such as the United Nations and the World Health Organization, the EPA in the US, and other agencies in the EU have assured since the 1990s that the substance is harmless to humans, this started to change after 2015 when the WHO admitted glyphosate was “probably carcinogenic” for humans. In Argentina, Dr. Andrés Carrasco denounced in 2009 the effects of agrotoxics on the population and the severe health risks they represented. He was heavily criticized by some sectors of the scientific community who argued that Carrasco had irresponsibly jumped to conclusions before his research could be properly evaluated. He admitted that while this was true, the problem was too serious to keep on waiting and instead chose to alert the public about the issue. The official version in Argentina still states glyphosate is harmless. Carrasco’s report was published in Chemical Research Toxicology in 2010. Web link to the document: http://reduas.com.ar/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2011/09/paper-carrasco.pdf (June 5, 2024).

18 The utopian aims of Sarmiento and his Latin American counterparts would soon be contested by the changes in their countries’ realities: “As the [19th] century turned, trends in non-utopian Latin American science fiction included a general movement away from optimism toward pessimism, and from technophilia to technophobia” (Haywood Ferreira 2011, 81).

19 Original: “Las ciudades que habían sido el motor semoviente de los proyectos de la modernidad futura del siglo xix se convierten en estas historietas en un espacio corrupto y corruptor, donde las normas de civilidad y empatía apenas sí pueden existir en ámbitos comunitarios muy acotados. La ética social ha desaparecido para ser reemplazada por las limitadas posibilidades de opciones individuales de dudoso alcance y corto plazo. Los sujetos ideales que habían sido el centro de la reflexión del discurso decimonónico sobre la nación deseada, en las historietas, capitulan o resisten sin esperanza, pero no son los sujetos idealizados del discurso populista preponderante en otros espacios del campo letrado” (Kurlat Ares 2015, 143; English translation by Pablo Turnes). Kurlat Ares’ text presents an interpretation opposite to this article’s perspective on Argentine sci-fi comics. The main problem is, first, the reductive and yet abstract use of the term “populism” [populismo], which the author never really defines clearly. And second, it is not clear how her interpretation of Diego Agrimbau’s and Gabriel Ippólitti’s works (La Burbuja de Bertold and Planeta Extra) can be directly linked to the “ills” of populism as a flawed and damaging political project. In this vein, her reading of said works seems too forced in her attempt to propose an extremely simplified –yet ideologically loaded– reading of modern and contemporary Argentine politics.

20 King and Page (2017: 23-44) do present a very interesting and valuable take on Salvador Sanz’s saga Angela Della Morte, from a different perspective to that of this article, but which can be understood as part of Sanz’s interests and topics present in his overall work.

21 In this same vein, King had previously proposed that “it is the science fiction genre that has become the vehicle for the most sustained critique of modernity in Latin America” (King 2013, 22).