DOI: 10.18441/ibam.25.2025.88.63-82

Melina Teubner

Universität Bern, Switzerland

Melina.teubner@unibe.ch

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-4990-2152

In 1992, Marcello Sandoli, the chairman of the National Association of Poultry Slaughterhouses (Associação Nacional dos Abatedouros Avícolas, ANAB), spoke of a drastic change in the nutritional practices of his country (Anuario 93, 24). Chicken meat, he said, had become an ubiquitous food in Brazilian households. In fact, national consumption increased from 13 kg per person in 1990 to a peak of around 40 kg in 20101. This rapid increase was only possible due to fundamental changes in urban consumption practices.

As a major exporter, Brazil had become very important as a supplier of cheap frozen chicken to the growing global population. Chicken meat is a food product that is marketed on a global scale by large agribusiness corporations in a neoliberal, cooperative food regime with its own specific consumption practices (Friedmann and Mc Michael 1989; Dixon 2002). The emergence of a high-tech, vertically integrated chicken industry, in which farmers contract with processors, has been studied in detail from a technical, biological, veterinary, and economic perspective (Souza et al. 2011). Historical research has paid attention to its importance for the international market (Klein and Vidal Luna 2022). One reason for this is the tendency to analyze the countries of the global south primarily as exporters, while the growth in consumption within these populations is almost neglected by researchers (for an overview of the research on different deficits, see Trentmann and Otero-Cleves 2017; Horner and Nadvi 2018). However, most of the production (since the mid-1990s around 70 percent) has been intended for domestic consumption (IBGE 2006). This massive increase in chicken consumption as part of changing urban diets over a decade in Brazil, especially in terms of local actors and perspectives, has been under-researched from a cultural studies viewpoint.

Building on these findings, this paper examines how the mass consumption of chicken meat developed in Brazil’s large cities during the 1990s. It also examines the role of local actors at different levels in popularizing chicken. Chicken was initially attractive because it had become very cheap, and the country was hit by a severe economic crisis in the early 1990s. However, this was far from the only reason for chicken’s popularity. The industry has fought hard against being seen only as a cheap beef alternative. This article argues that chicken became popular in Brazil through its multiple meanings, making chicken attractive to almost everyone in highly unequal cities (see on this Dixon 2002; Kollnig 2022). The object here, therefore, is to describe the different meanings attributed to food by different social classes, meanings that are considered to be highly important in making everyday food choices. The transformation of the industry, however, was not just about the product, but also about changing supply strategies, the specific consumption sites that were crucial in the 1990s, and, alongside the existential supply of food, (taste) experiences and entertainment.

Articles from the magazine Aves & Ovos, published by the Association of Chicken Producers of São Paulo between 1990 and 2000, are analyzed. These articles make it possible to reconstruct important changes in chicken consumption in large Brazilian cities in the south and central south of the country (Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Curitiba) in relation to political, social, and economic developments of the 1990s. The authors were usually men from the upper middle and upper classes, writing for a corresponding readership. To broaden this perspective, this article also includes findings from qualitative interviews. As part of a larger study on chicken consumption in cities of the Mercosur, I spoke to a number of producers, but above all consumers from various social backgrounds, about their eating habits and how these have changed since the 1990s.

The first part of the paper looks at the promises of urban consumption during a severe economic crisis in the early 1990s. Subsequently, I analyze changing consumption habits and practices, considering contemporary discourses on (good) food, health and modernity. (New) sites of chicken consumption are identified in the third section. Finally, I discuss the marketing strategies that promoted the rise of mass chicken consumption.

In the early 1990s, Brazil suffered a severe economic crisis which also threatened to undermine the country’s food security. In her article in this dossier, Jennifer Adair demonstrates the impact of food insecurity caused by an economic crisis, using the example of real and imagined food riots in Buenos Aires. Such political turmoil was to be avoided in Brazil. Political and business leaders met to discuss how to improve the situation through the provision of cheap food for the country’s growing urban population. In 1970, Brazil’s urban population comprised 56 percent of the country’s total; by 1990 it had already reached 75 percent and has risen even further since (Aves & Ovos 1995a, 14). At the same time, chicken production had become a highly competitive industry, pioneering large-scale intensive livestock production in Brazil. By the early 1990s, it was able to offer meat at increasingly low prices (1974: 4.50 R$ (reales2), 1994: 1.25 R$ average/kg) (Aves & Ovos 1997, 7). The chicken has undergone a fundamental change: it has become an industrial product. The entire production is still based on certain high-performance breeds. The fattening period of these animals has been reduced, as has the amount of feed an animal needs to grow until it is ready for slaughter. This is why the poultry industry has played a very active role in discussions on improving food security. A reduction in the cost of food, through efficient production and low taxes, is intended to make food cheap enough to be affordable for all sections of the population. The developments in agriculture were by no means uncontroversial, as the large, well-funded farming businesses were favored over the smaller ones. Backyard chicken farming for subsistence and sale at local markets had been common in Brazilian cities for centuries (Debret 2014, 187-188), but as urbanization has increased, this practice has continuously declined. Regulations and hygiene standards have been tightened, with less time for housework due to working hours, and people tend to live in cramped, garden-less housing. A woman who grew up in the north of Rio de Janeiro highlights the increased dependency on the food industries as the number of people able to produce foodstuff in their own gardens has decreased:

In the old days, houses weren’t like they are today, when they’re very small and we build on top of them. Making buildings, right? In the old days, it was a house with a yard, there were pigs, you know, chickens, mallards, and ducks, there was all that, plantations that my father, my grandfather also used to plant vegetables […] (Interview, Curitiba, November 2023).3

With the Plano Real (a currency reform adopted in early 1994 to end the high inflation of the early 1990s), the then Brazilian president Fernando Henrique Cardoso promised the population that they would eat more chicken. A kilogram of chicken then cost exactly one real (Cury 2014). Years later, many Brazilians still remembered Cardoso’s consumer promise. Industrially-produced chicken became a symbol of Cardozo’s policies, promising people a better economic future.

Before the modernization of the chicken industry, chicken meat was expensive and was therefore only eaten by many families at weekends or on public holidays. For centuries, it was considered excellent food for the sick (Wätzold 2011, 95). It is difficult to generalize about what was eaten in Brazil in the past, given the regional differences and the considerable social inequalities and differences in financial resources. Rice and beans were consumed daily across all social classes and in all regions. Beans, as an article from the 1990s mentions, were labelled in the past the “meat of the poor” because they are a very cheap vegetable protein (Aves & Ovos 2003, 26). The aim of the chicken industry was that their product, as the cheapest animal protein, should have a similar status to beans. Aves & Ovos therefore compared the nutrient content (protein and energy) of chicken meat with that of boiled black beans, along with a comparison of the respective prices, to present both foods as equivalent. The whole chicken was not much more expensive than the beans, and animal proteins were considered to be of higher quality (Aves & Ovos 2003, 27). Animal protein became an integral part of the meals of a larger number of people and took on an increasingly important role in people’s vocabulary. The word protein entered the language as a synonym for meat: this further distances language from its association with an actual animal, and also indirectly hinders the association of the word with non-animal alternatives, while emphasizing the importance of satisfying a basic physical human need.

The price of chicken varied considerably, depending on what form it was sold in and how much processing it had undergone. In 1992, 55 percent of chickens was still sold in the form of the whole bird. This preference can be explained due to the low price (Avicultura & Suinocultura Industrial 1992b, 4). Nevertheless, there was already a trend towards buying individual parts, with 43 percent of chickens being sold in portions in 1992. In the population, a general trend can be observed from larger to smaller households, encouraging the purchasing of smaller portions of meat (Avicultura & Suinocultura Industrial 1992b, 4). It was also time-saving to buy individual pieces, which were quicker and easier to prepare. Finally, culinary preferences played a role, as consumers could buy the parts they preferred. Some of the people interviewed for this article described it as a very present childhood memory that disputes arose between them and their siblings over the question of who got to eat which part of the chicken. Such conflicts could be avoided by buying just the thighs and drumsticks, which are very popular in Brazil.

The chicken industry also began to develop a greater variety to increase the profit margins of the product, as the individual parts were more expensive to sell than the whole chicken. These were mostly products that already existed abroad, adopted by and adapted to the Brazilian market. At the beginning of the 1990s, a small percentage (2 percent) of chicken began to be sold in the form of processed products such as hamburgers, nuggets, or sausages by the large chicken companies (Avicultura & Suinocultura Industrial 1992b, 4). This significant change prompted the magazine Avicultura & Suinocultura Industrial to publish a cover in November 1992 with the caption “Processed products reach the consumer’s table” (Avicultura & Suinocultura Industrial 1992b, cover). Sadia, the main chicken producer at the time, created a turkey mascot in 1971. As shown in a fiftieth anniversary commercial, Lek Trek helped Sadia introduce the new processed products to consumers through television advertising.4 (Comercial Sadia 2021).

Chicken meat developed in the 1990s from a food that was eaten on Sundays and festive days to a food that most of the population consumed at least twice a week (Aves & Ovos 1995b, 38). The changes in consumer behavior were linked to urban living habits. More women worked outside the home (Camargo Andrade [2004] investigates changes that took place in the 1990s and focuses on the role of women in it). One author expressed the changes as follows:

Whether it’s due to a lack of time or convenience is not so important. The fact is that housewives in the home want more and more family meals that are naturally tasty but easy to prepare, healthy and of high quality in terms of nutritional content and hygiene. It would be all the better if these characteristics were guaranteed and the food was already prepared and only needed to be heated in the microwave for a few minutes (Aves & Ovos 1995e, 9).5

The author mentions the influence that women had in the choice of food, because in most cases women were responsible for shopping and cooking (cf. Miller 1995, 9; Dixon 2002, 17, 60, 63). However, he fails to mention that women were also ambivalent about the increasing reliance on industrialized convenience foods to feed their families. Due to the double burden of employment and household chores, women were disproportionately dependent on these products from the food industry, even if they were critical of the processes behind them and would have preferred to cook fresh meals for their families. Carole Counihan has shown that Italian women in the period since the Second World War were very ambivalent about losing control over the provision of food for their families (Counihan 1988, 58). In Brazil, the process was even more complex because a significant proportion of women worked for other families in a domestic role. Consequently, this results in a reduction in the time available for the care and nurturing of their own families (Camargo Andrade 2004).

The growing need for simple dishes was presented as a complete contrast to the traditional preparation of live chickens, something that had been very common before the 1990s. In an article on the fiftieth anniversary of industrial chicken production, Aves & Ovos published a report that used the character, “Dona Izabel,” to show how much more difficult it supposedly was for housewives when chicken meat was not yet mainly sold in supermarkets and the housewife prepared a chicken for the family on Sundays (Aves & Ovos 1994b, 24-25). The report emphasized the amount of time involved; the chicken either had to be bought alive or came from the family’s own small flock, and then, the process of butchering required a certain amount of knowledge and experience that the author alleged housewives did not have: “Butchering chickens was a technique that even the most dedicated housewives could not master” (Aves & Ovos 1994b, 24). This statement should, of course, be seen against the background of the industry’s desire to sell its products. In fact, the knowledge of how to slaughter chickens had been around for centuries.

It was true, however, that this was a violent and bloody process; the feathers and inedible parts had to be removed before the chicken could be cooked. When buying chicken meat in supermarkets, by contrast, consumers are shielded from the reality of killing and the transformation of the chicken from a living being to a commodity. This was advantageous to the chicken industry, as compared to industrial production, the traditional process could be represented as unhygienic and backward. Buying chickens through supermarkets, markets and butchers meant less visible violence, labor, effort, and dirt. Modern industrial production was thus defined in terms of its difference to the violent killing of chicken in households.

On the other hand, however, it also meant increasing dependence on the food industry. A fifty-year-old chiropodist who now lives in Curitiba associated keeping chickens for self-sufficiency with the fact that she always had something to eat when she was growing up in the north of the city of Rio de Janeiro, as she told me in an interview:

We used to eat like this, we didn’t buy the chicken, not at the market. We bred chickens at home [...] basically everyone had chickens in the house, and if you have chickens, you have eggs, so there’s a lot of egg consumption. So that’s the case everywhere, isn’t it? So, you don’t have to starve. If you have the chicken in the house, then you basically have the egg and the chicken. When it gets old, it’s killed and goes into the pot to be cooked. The chicken can reproduce, can’t it? It’s the easiest and cheapest meat we have (Interview, Curitiba, November 2023).6

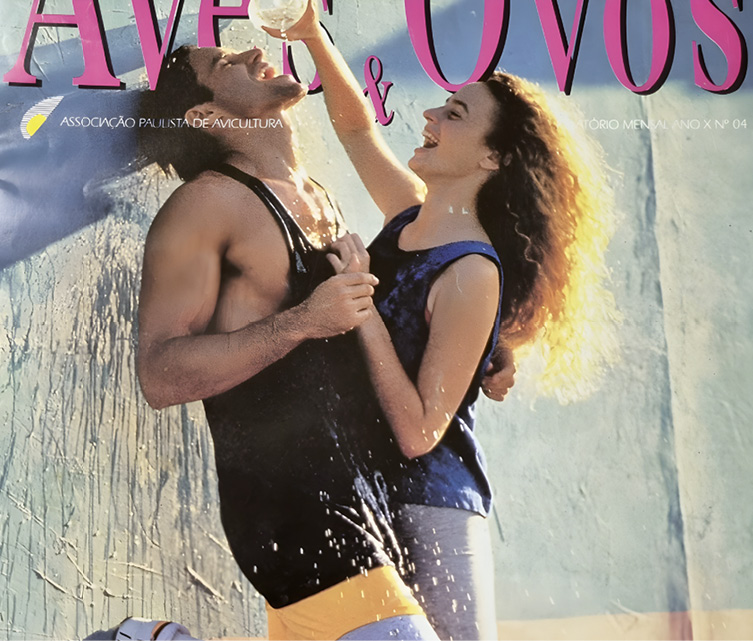

The chicken industry did not only market chicken meat as a cheap protein. It also successfully promoted the global trend of consuming white meat among the more affluent classes in Brazil. In these discourses, the health aspect was placed in the foreground. This was summarized in an article on chicken consumption: “By and large, consumers [in “developed countries”] are increasingly looking for foods that improve their health, are considered healthy and can help prolong life” (Aves & Ovos 1999, 24). Nutritional science has been instrumental in promoting this image, emphasizing the high energy and lower fat content of chicken compared to other meats. Nutrition became an important topic for experts, who declared what was good and what was not good and thus influenced people’s everyday lives in a form of social control (Dixon 2002, 15). A parallel development to the consumption of chicken meat was the fitness trend first adopted by the middle and upper classes (see figure 1).

Chicken became synonymous with an ideal diet for athletes (Aves & Ovos, 1994c, 14f.). It is therefore not surprising that the first “Chicken Light” range was advertised in an expensive television campaign in 1991 (Avicultura & Suinocultura Industrial 1992a, 48).

Against this background, chicken breast also became more popular and was already the most popular part of the chicken on the European market and in the USA. In a promotional video from 2022, Brazilian football player Neymar appears together with the Sadia chicken Lek Trek to advertise the consumption of the products of one of Brazil’s best-known chicken brands.7 Both the football star and the chicken itself are presented as up-and-comers, one from poverty as a role model for many young people, the other as a representation of a species that is otherwise namelessly intended for consumption. The problems caused by industrial production are faded out by people dancing happily in the city, eating various snacks in everyday situations. All of this is bathed in Brazil’s national colors, with both Sadia and Neymar staged as figureheads of a “modern” urban society.

The consumption of processed products in advertising and the association with elite sport initially seems paradoxical. But the commercial unintentionally opens a revealing perspective: both the chicken and Neymar stand for the extreme optimization of bodies in neoliberalism, described by Jürgen Martschukat as follows: “The actions of subjects must be geared toward investing in themselves in order – always and everywhere – to increase their own “portfolio value.” The goal is for these investments and one’s work on oneself to yield visible results. Such evident success enables individuals to be recognized as productive members of society. Consequently, in neoliberalism the relationship between individual and society is measured in a new way.” (Martschukat 2021, 15) This common connection in advertisements points to what social geographer Julie Guthman calls the “bulimic” relationship promoted by the current food regime, characterized by a demand for lean and powerful bodies and a simultaneous ubiquity of highly processed products offered at ever lower prices (Guthman 2011, 163-184; Martschukat 2021, 21f.).

The emerging distinction between healthy and unhealthy, to which chicken breast owed its reputation as a high-quality source of protein, labelled chicken skin as unhealthy because it was considered too fatty. In one of my interviews in Curitiba, a pensioner who had worked in the health system herself deliberately mentioned the aspect that she no longer eats chicken skin for this reason. However, as she had previously told me how much she loves all parts of the chicken, it is possible that she wanted to emphasize to a foreign scientist (me) that she knows the advice of nutritionists and follows it. The death of her husband had in any case made her think about healthy eating, as he had died “not because of the chicken, of course, but because of the whole diet (Interview, Curitiba, November 2023).” To a certain extent, however, such a statement is indicative of a viewpoint in which the reasons for an unhealthy diet and lifestyle are sought in individual failures and not in social problems, in a society in which nutrition has also become an indicator of class distinction (Martschukat 2019, 43).

Upper-class and upper-middle-class consumers can opt for expensive niche products whose production is subject to mandatory regulations to enable them to be labelled and sold as free-range or organic chickens. In the 1990s, there were hardly any products for this sector. An article in Aves & Ovos presents a brand of chickens from France that were reared under better conditions, as certified by the state, and slaughtered after a longer period. The article discusses whether such niche products would also be suitable for the Brazilian market, where there was also a certain demand for more expensive products (Aves & Ovos 1998, 12). Organic chicken was not yet sold in supermarkets in the 1990s, although people could buy them from local markets. This made it possible to continue small-scale production without falling victim to the pressure from large corporations, as was later the case (Interview, Curitiba, November 2023.)8 In 1994, the Korin brand was founded, which is important for the organic sector and is based on Mokiti Okada’s philosophy and method of natural farming (Korin 2024). To date, organic and free-range production has developed to such an extent that all major brands have included it in their product range. The current food regime has not been fundamentally changed by these developments, but critical forces have been integrated into the system (Martschukat 2019, 35). In the interviews I conducted, a certain skepticism was expressed towards free-range chickens bought in supermarkets, which in the end also came from industrial production. They are said to have lost the better flavor of a “galinha caipira,” which many still associate with their childhood, when their mother or grandmother slaughtered a chicken on Sundays and the whole family came to eat (Interview, Niterói, October 2021).9 So despite the story of „Dona Izabel“ told by the chicken industry there is still a nostalgia for the traditional ways of eating the “galinha”.10

Most food has been sold via supermarkets since the 1990s. The supermarket revolution, as it has been called in research, was faster and more intensive in Brazil than in other regions. Between 1990 and 2000, the share of products sold through supermarkets increased from 30 percent to 70 percent (Niederle and Wesz Junior 2018, 114). Large supermarket chains such as the French company Carrefour and the Brazilian company Pão de Açúcar dominated the market. Despite the rapid and intensive expansion of supermarkets, meat continued to be sold via poultry farms, street markets, butcheries, farm shops and municipal markets (see table 1).

As an everyday product, chicken meat was an important product for supermarkets, attracting customers and generating high profits compared to other products (while it occupied only 0.6% of the display area in supermarkets, chicken accounted for 3.7% of total supermarket sales see Aves & Ovos September 1993c, 12; Aves & Ovos 1992b, 18). During certain periods in the 1990s, companies were sometimes unable to supply enough chicken meat to supermarkets to fulfil the high demand, as the head of marketing at Copacol remembered (Interview, Cafelândia, December 2023). The market power of the supermarkets meant that they could set the prices: for example, producers continue to object that it is made more difficult for the lower-income population to buy food because the mark-up in supermarkets is too high. This tendency is least visi-

|

Equipment |

POF FIPE 1981/82 (1) |

POF FIPE 1991/92 (1) |

APA 1994 (2) |

|

Supermarket (Supermercado) |

19 |

34.5 |

35 to 40 |

|

Poultry farm (Avícula) |

31 |

39 |

20 to 25 |

|

Street market (Feira) |

15 |

13 |

15 |

|

Butchery Açougue |

12.5 |

n.c. |

n.c. |

|

Farm (Granja) |

10.3 |

n.c. |

n.c. |

|

Town markets (Mercados |

4.2 |

n.c. |

n.c. |

|

Others |

8 |

3.5 |

5 |

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

ble in the case of a whole chicken: a whole chicken in 2003 was available in stores for R$2.50, whereas the wholesale purchase price was R$1.80, a markup of 9 percent on the original price (Aves & Ovos 2003, 28).11 However, the markup for chicken breast in the supermarket was 82 percent (R$5.29 at the supermarket compared to R$2.90 wholesale). For drumsticks, the retail price was twice as high as the wholesale price (R$4.19 compared to R$2.10). The producers criticized the very high profit margins of the retail trade within the chicken supply chain because they had most of the work and bore a much higher risk. By increasing productivity, they can offer products at ever lower prices to supermarkets, but these price reductions are not passed on to customers to a sufficient extent (Aves & Ovos 2003, 28).

Curitiba, a city that is considered a national role model in terms of food security projects, has attempted to limit the power of the supermarkets to some extent using different control strategies, thereby giving a greater number of people access to food in general, including chicken meat. A wide range of weekly markets was set up in different parts of the city and at different times. In the 1990s, prices of basic foodstuffs in the city’s main supermarkets on a weekly basis were compared and published to guarantee greater price stability and ensure a certain control function vis-à-vis the supermarkets (Interview, Curitiba, November 2023). Furthermore, so-called “Armazéns da familia” (Family stores) were opened in various neighborhoods. In the early years, these were older, converted buses that travelled to the city districts to sell food to parts of the population. The prices of the Armazém food were on average 30 percent cheaper than the food on offer in the supermarkets. Initially, people earning up to three times the statutory minimum wage12 a month benefited from this project; later, people earning up to five times the statutory minimum wage a month were also able to benefit.13 Social policy therefore played an important role in ensuring that chicken meat reached all levels of society and that Cardoso’s promise of consumption could be fulfilled.

A decisive change took place on the labor market, too. Employees lived on the outskirts of growing cities and had long journeys to get to work; there was no time to go home during the break, so they had to be catered for (Aves & Ovos 1995d,14). In order to increase the productivity of the employees and to integrate them more strongly intothe company apparatus, they were often given the opportunity to eat together (see figure 2; Bernet 2016, 273; Tanner 1999).

In the 1990s, the provision of food for the workforce was professionalized and the provision of thousands of lunches was outsourced to external companies. In collaboration with nutritionists, weekly menu plans were drawn up that had to fulfil several functions: first, the food had to taste good to the workers and be available in sufficient quantities. In addition, a balanced meal was to be offered to promote the health and thus the performance of the workers. Rice and beans were on the menu almost every day. Chicken was on the menu about twice a week, in various forms. Chicken with noodles or polenta was very popular in the canteens and was a typical dish from the south of the country, reminding the workers of home cooking (Aves & Ovos 1991c, 5-6). The situation was similar in the university canteens, which not only offered lunch, but where students could eat all day for very little money. Here, too, the nutritionists included chicken several times a week. In one of the large canteens in Curitiba, one of the decisive developments in the 1990s was that whole chickens were no longer purchased, but rather individual chicken parts for different dishes. According to the current head of the canteen, this was much more popular with students than the whole chicken (Andrade Grácia, 2000; Interview, Curitiba, November 2023). This corresponds to the trend described above for private households. Chicken stroganoff with fried potato sticks became a classic. The chicken industry considered it a particularly great success that chicken meat was also included in school meals. Children were to receive several meals a day at school, depending on the education plan, to cover part of their daily requirements at school (see figure 3; Aves & Ovos 1991a, 5-9).

Guaranteeing communal catering as part of social policy meant a huge logistical effort. The amount of food cooked every day in communal catering, in addition to increasing consumption at home, helped the industry to achieve high consumption volumes of 22 kg per capita in the state of Paraná, 20 kg in Rio de Janeiro, and 18.5 kg in São Paulo in the year 1997 (Avicultura & Suinocultura Industrial 1991b, 54).

At the same time, restaurants sprang up offering pay-by-weight buffets (Aves & Ovos 1995c, 72). These restaurants were mainly visited during the lunch break: it was quicker than ordering à la carte and could also be cheaper if only a small amount was scooped onto the plate. In addition, (inter)national fast-food chains tried to assert themselves on the Brazilian market in the big cities and integrate chicken into their range (Aves & Ovos 1991b, 5-9). Even the fast-food chains used the discourse that chicken was healthier, to market it as a better alternative to beefburgers. The beef supply chain was not as productive as the chicken chain at the time, but consumer demand for burgers was still very high. For the fast food restaurants, the integration of chicken into their menu was therefore a necessity in order to be less dependent on the beef industry, which could not supply enough meat at certain times (Aves & Ovos 1991b, 6). McDonalds tried in 1979 to gain a foothold in large Brazilian cities. In 1991, there were 70 McDonalds outlets throughout Brazil. They launched expensive advertising campaigns on television to appeal to children with the clown Ronald McDonald, but most of the population in the 1990s simply could not afford a visit to McDonalds as a leisure activity, which led it to become a place of consumption for the upper middle class. Nevertheless, McDonalds influenced children from other social classes in their consumer dreams, as comments under the old McDonalds adverts on YouTube show: “I grew up watching it, but we could never afford to buy such a delicious sandwich. I bought my first when I got my first job at the age of 14”.14 Between 2008 and 2013 McDonalds became more popular and the composition of customers changed, with more people from the so-called new middle class, now able to afford a visit and making up 40 percent of regular customers (Mundodomarketing 2013).

However, Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC)—a brand that was vital to the creation of mass consumption of chicken in Australia—failed in Brazil in the 1970s. A new attempt was made in the nineties, when Pedro Conde Filho, a son of a wealthy banking family, tried to establish the fried chicken franchise in Brazilian cities. Despite the owner’s financial strength, however, this endeavor was only moderately successful (Aves & Ovos 1993b, 34). What Jane Dixon found to be so central to the distribution of chicken in Australia did not work in Brazil. KFC, unlike McDonalds and national chains such as Bobs, never really became popular in Brazil and still has only a few outlets across the country. Bobs was the first national chain to open its first shop in the Copacabana neighborhood back in 1952 and introduced the franchise system in 1984 (Bob’s 2022). Like McDonalds, it was intended to appeal to families and young people as a target group. Since the 1970s, the chain has also been offered dishes with chicken, such as the Chicken Sandwich or the Chicken Salad. Here, too, there is a connection to top-class sport, as the chain was founded by a former professional tennis player.

Another place where chicken is typically consumed today, which was reserved for the upper classes back then, is the airplane. Chicken was first included in the menu selection of Brazilian airlines in the 1990s and was very well received by customers. At that time, travelers received a proper menu on domestic flights (Aves & Ovos 1992a, 6-12).

The chicken breeders’ association described these changes in daily food consumption as the “conquista” of the chicken, which conquered canteen, restaurants, private households, fast-food outlets, and even airplanes in a relatively short space of time (Aves & Ovos 1994a, 11).

In the 1990s, the chicken industry started to think about joint marketing strategies (Aves & Ovos 1993a, 5-10). With the production side of the business perfected, the focus turned to improving other parts of the supply chain. This included a campaign to increase the popularity of chicken as a mass consumer product, rather than just promoting individual brands. The model was a successful campaign that increased consumption of apples in Brazil from 600 grams to 3.6 kg per person per year. Organized by major advertising agencies, the campaign included supermarket promotions, TV and radio advertising, and the handing out of recipes in supermarkets.

Large companies such as Sadia and Perdigão, with experience in marketing their products abroad, were the leaders in marketing and product promotion. They were also the only ones that could afford to advertise their products on a large enough scale to keep the brand in people’s minds. Perdigão became famous with a particular product. The “Chester,” developed in 1982, became a bestseller and countless families included it in their Christmas menus in the 1990s (Aves & Ovos 1992c, 17). Television advertisements at the beginning of the decade promoted “Chester Perdigão, the new Christmas tradition”.15 What made Chester special was that the most popular parts (breast, leg, and thigh) accounted for over 70 percent of the whole chicken. Perdigão promoted the fact that it was smaller than a turkey, which made it ideal for a family to eat and easier to cook in the oven.

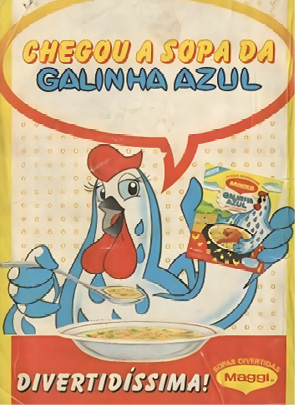

One of the most aggressive product advertisements was by Maggi, which wanted to push the marketing of its chicken stock cubes, especially against the competition from Knorr. The “Galinha Azul” was born. By the end of the 1980s, the “blue chicken” was dancing in carnivals, appearing in various shows and advertisements, and was the subject of a special edition of Playboy. The chicken danced to a jingle with animated crowds: “From east to west, from north to south. The wave is the dance of the blue chicken”.16 In all these adverts, silliness was used as a communication strategy to attract the attention of potential consumers. Using the example of Milka chocolate’s purple cow, art historian Walter Grasskamp has argued that silliness has been the predominant mood in product advertising in recent years (Grasskamp 2000, 122). He attests to the remarkable suggestive power of silliness as an aesthetic phenomenon:

Unlike satire and parody, in which the circumstances to which they owe themselves are always inscribed, silliness makes life appear unclouded, as if there were no serious problems at all, as if the world had no weight: it creates a playful context in which nothing demands to be taken seriously; it is the pure surface of comedy, without the rich connotations of irony or cynicism; an almost autonomous firework for which reality serves at most as a fuse. As such, it can be a state of happiness, albeit only for a short time, because the secret of its aesthetic effect lies in its dosage and integration into the other genres of the comic (Grasskamp 2000, 122).17

However, the state of happiness described by Grasskamp can only be felt by those who ignore real animal suffering. The animals are not perceived as living beings and individuals, but sympathetic representations that advertise eating their fellow species. An important aspect shown in the adverts is the fun and entertaining effect of eating. In this context, the adverts targeted new consumer groups such as young people and children, with products designed especially for them. A chicken sausage labelled Mônica after the popular Brazilian comic series “Turma da Mônica” won a marketing award in Paris in 1991 (Avicultura & Suinocultura Industrial 1991a, 28-29). Chicken alphabet soups were sold in Maggi’s “Fun Soups” range and marketed by the Galinha Azul or the then child star XUXA. The packaging of the soup featured a whole chicken or a chicken wing lying on the alphabet soup (see figure 4). This was intended to make the consumer associate the highly industrialized product with chicken soup prepared at home.

Most companies could not afford these large-scale campaigns. One of the marketing directors of a large company told me in a conversation that he commissions marvelous marketing studies that bring wonderful results to light. However, in his many years’ experience, people are ultimately only interested in three things: the appearance of the product, good quality and, most importantly, the favorable price (Interview, Cafelândia, December 2023). The campaigns helped these companies with the aim of increasing overall consumption, whereby the individual brands, apart from the biggest brands, are still rather interchangeable for consumers today.

The 1990s were extremely important for the establishment of mass consumption of chicken meat in Brazilian cities. The ability to produce chicken meat more cheaply gave more people access to this inexpensive “protein.” The promise of consumption made by President Cardoso at the time became a reality for large sections of the population. The supply of chicken meat changed fundamentally from household production to purchase via markets and, to an ever greater extent, to retail sales via supermarkets. In the same period as the chicken industry, supermarkets also became more influential. They tried to lure customers into the stores with chicken meat offers and various promotions. They had a lot of power when it came to setting prices. In Curitiba, an attempt was made to weaken this power somewhat by making it possible for people with lower incomes to shop for chicken in alternative supermarkets with the aim of contributing to the food security of the population. In a very unequal urban society, chicken meat developed into a food that was eaten by everyone in the 1990s. On the one hand, it became as relevant as the staple foods, rice and beans. On the other hand, it was and is associated with (new) leisure activities designed for fun and personal well-being. The chicken industry has succeeded in attributing these many different meanings to chicken, making it popular for different reasons. This omnipresence in all social classes and milieus—whose individuals differed greatly in their purchasing power and consumption practices in other areas—was the real success of the chicken and led to the high sales figures (more than in many other regions of the world). The inclusion of chicken meat in people’s dietary practices was not an automatic process that can be explained solely by a global trend, but local actors worked in many areas to make chicken meat attractive through many specific components in Brazilian cities. The increase in chicken meat consumption is told in Brazil as a success story in which the problems of violent production with regard to animal welfare, working conditions, and environmental destruction are ignored. Therefore, there is still need of further critical historical research on this subject, in order to elucidate the ambivalence of increasing consumption.18

Anuario’93 da Avicultura & Suinocultura Industrial, October 1993, 24.

Aves & Ovos. 1991a. “Frangos e ovos conquista a merenda escolar.” Aves & Ovos, February 1991.

Aves & Ovos. 1991b. “Frango Conquista a rede Mcdonald’s.” Aves & Ovos, September 1991.

Aves & Ovos. 1991c. “Frango enriquece cardapio dos trabalhadores.” Aves & Ovos, October 1991.

Aves & Ovos. 1992a. “Frango invade o cardápio dos aviões.” Aves & Ovos, January 1992.

Aves & Ovos. 1992b. “Frangos e Ovos nos Supermercados.” Aves & Ovos, January 1992.

Aves & Ovos. 1992c. “Os 10 anos do chester”. Aves & Ovos, September 1992.

Aves & Ovos. 1993a. “A grande sacada do frango.” Aves & Ovos, September 1993.

Aves & Ovos. 1993b. “A importancia do Fast Food na área de alimentos.” Aves & Ovos, September 1993.

Aves & Ovos. 1993c. “A cara do frango no supermercado e sugestões para ampliar as vendas.” Aves & Ovos, September 1993.

Aves & Ovos. 1994a. “Ano do frango na mídia.” Aves & Ovos, February 1994.

Aves & Ovos. 1994b. “Crônica das penas de Dona Izabel às voltas com almoço de domingo.” Aves & Ovos, December 1994.

Aves & Ovos. 1995a. Aves & Ovos, February 1995.

Aves & Ovos. 1995b. “Campanha do frango agrada consumidores.” Aves & Ovos, January 1995.

Aves & Ovos. 1995c. “Americanos comem fora e dispensam o garcom.” Aves & Ovos, February 1995.

Aves & Ovos.1995d. “Este ano, mais frangos e ovos no dia-a-dia.” Aves & Ovos, February 1995.

Aves & Ovos. 1995e. “A vida mais facil para o consumidor.” Aves & Ovos, July 1995.

Aves & Ovos, 1997. Aves & Ovos, March 1997.

Aves & Ovos. 1997. “Preços médios por kg da carne de frango no varejo de 1974 a 1994.” Aves & Ovos, Abril 1997.

Aves & Ovos. 1998. “A etiqueta do caipira francês.” Aves & Ovos, August 1998.

Aves & Ovos. 1999. “O frango na ponta do consumo.” Aves & Ovos, August 1999.

Aves & Ovos 2003. “Frango: Alimento nutricionalmente diferenciado.” Aves & Ovos, April 2003.

Avicultura & Suinocultura Industrial. 1991a, February.

Avicultura & Suinocultura Industrial. 1991b, December.

Avicultura & Suinocultura Industrial. 1992a, June.

Avicultura & Suinocultura Industrial. 1992b, November.

Bernet, Brigitta. 2016. “Insourcing and Outsourcing. Anthropologien der modernen Arbeit.” Historische Anthropologie 24 (2): 272-293.

Counihan, Carole M. 1988. “Female Identity, Food, and Power in Contemporary Florence.” Anthropological Quarterly 61 (2): 51-62.

Cury, Anay. 2014. “Frango e iogurte são símbolos do Plano Real; veja dez curiosidades.” Globo, July 1. https://g1.globo.com/economia/noticia/2014/07/frango-e-iogurte-sao-simbolos-do-plano-real-veja-dez-curiosidades.html (Feburary 14, 2024).

de Andrade Grácia, Marilice. 2000. Redução do custo dos pratos protéicos dos restaurantes universitários da universidade federal do Paraná. Universidade Federal do Paraná.

Debret, Jean-Baptiste. 2014. Voyage pittoresque et historique au Brésil. Actes Sud.

Dixon, Jane. 2002. The Changing Chicken. Chooks, Cooks, and Culinary Culture. University of New South Wales.

Empresa Bob’s. 2022. Bob’s Rumo aos 70 anos. O primeiro hambúerger do Brasil. Lamonica.

Grasskamp, Walter. 2000. Konsumglück. Die Ware als Erlösung. C.H. Beck.

Guthman, Julie. 2011. Weighing In: Obesity, Food Justice, and the Limits of Capitalism. University of California Press.

Horner, Rory, and Khalid Nadvi. 2018. “Global Value Chains and the Rise of the Global South: Unpacking Twenty-First Century Polycentric Trade.” Global Networks 18 (2): 207-237.

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia et Estatistica (IBGE). 2012. Censo Agropecuário 2006, Brasil, Grandes Regiões e Unidades da Federação. Second count. IBGE.

Klein, Herbert S. and Francisco Vidal Luna. 2022. “The Emergence of Brazil as the Leading World Exporter of Chicken Meat.” Historia Agraria de América Latina 3 (2): 75-99.

Kollnig, Sarah. 2020. “Chicken for Everyone? A Cultural Political Economy of the Popularity of Chicken Meat in Bolivia.” Gastronomica 20 (4): 36-48.

Korin. 2024. https://certifiedhumanebrasil.org/empresas-certificadas/korin-agropecuaria/. (February 14, 2024).

Martschukat, Jürgen. 2019. Das Zeitalter der Fitness. S. Fischer.

Martschukat, Jürgen. 2021. The Age of Fitness, How the Body came to symbolize success and Achievement. Polity Press.

Miller, Daniel. 1995. “Consumption as the Vanguard of History.” In Acknowledging Consumption: A Review of New Studies, edited by Daniel Miller. Routledge.

Mundodomarketing. 2013. “McDonald’s passa de 25 para 40% de clientes da Classe C e quer mais”. https://www.mundodomarketing.com.br/mcdonalds-passa-de-25-para-40-de-clientes-da-classe-c-e-quer-mais/ (Feburary 14, 2024).

Niederle, Paulo Andre, and Valdemar João Wesz Junior. 2018. As novas ordens alimentares, Editora da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul.

Strasburg de Camargo Andrade, Adriana. 2004. “Mulher e trabalho no Brasil dos anos 90.” Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Instituto de Economia.

Souza, Jean Carlos Porto Vilas Boas, Direceu João Duarte Talamini, Gerson Neudi Scheuermann, and Gilberto Silber Schimidt. 2011. Sonho, desafio e tecnologia: 35 anos de contribuições da Embrapa Suínos e Aves. Embrapa.

Tanner, Jakob. 1999. Fabrikmahlzeit. Ernährungswissenschaft, Industriearbeit und Volksernährung in der Schweiz, 1890-1950. Chronos.

Trentmann, Frank, and Ana María Otero-Cleves. 2017. “Presentation. Paths, Detours, and Connection: Consumption and Its Contribution to Latin American History”. Historia Critica 65: 13-28.

Wätzold, Tim. 2011. Vom kaiserlichen Koch zum nationalen Koch, Ernährungsgeschichte des brasilianischen Kaiserreichs. Proklamierung der “brasilianischen Küche” als Teil des nationalen Identitätsbildungsprozesses im Kaiserreich Brasilien 1822-1889. Brasilienkunde Verlag.

Manuscript received: 08.05.2024

Revised manuscript: 29.11.2024

Manuscript accepted: 19.12.2024

1 OECD, Data Meat consumption, 2023. https://data.oecd.org/agroutput/meat-consumption.htm (Feburary 14, 2024).

2 The Brazilian currency, introduced in July 1994 and still used today (in 1994 the value of US$ was 0.64 R$). Before 1994 the Brazilian currency was the Cruzeiro.

3 Translation from the Portuguese original.

4 Comercial Sadia - Lek trek: 50 anos de inovações pra você, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WGYtcXh8mNs, (viewed on February 14, 2024).

5 Translation from the Portuguese original.

6 Translation from the Portuguese Original.

7 Commercial Sadia, Lek Trek e Neymar “Sua torcida pede Sadia”, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_LXeernL6yo (February 14, 2024).

8 Interview with a vendor who sells Korin’s goods at an organic market. His parents used to produce organic chickens themselves.

9 Similar feelings were reported in many interviews.

10 In Brazilian Portuguese, these chickens are referred to as “galinhas,”and not as “frango,” a word used only for industrialized chickens.

11 In 2003 the value of one US$ was 3,07 R$.

12 The legal minimum wage was 70 R$ in September 1994. It rose steadily in the following years. (May 1995, R$ 100; May 1996, R$ 112; May 1997, R$ 120; May 1998, R$ 130; May 1999, R$ 136).

13 Armazém da familia, 2024. https://www.curitiba.pr.gov.br/servicos/armazem-da-familia/26 (February 14, 2024).

14 @cardosocardoso689, 2022, under the McDonalds commercials of the 1990s. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U2XMZvYfpsQ (February 18, 2024).

15 Comercial Perdigão - A Nova Tradição do Natal, 1994 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f95NQ0OrvP8 (viewed on February 16, 2024

16 Comercial Dança da Galinha Azul - Viva a Noite, 1991. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gNxM5pa0uCE (February 19, 2024).

17 Translation from the German original.

18 The author is currently working on major research project on the history of chicken consumption in the Mercosul in a global context, based at the University of Bern.