DOI: 10.18441/ibam.25.2025.88.83-100

Christiane Berth

Universität Graz, Austria.

christiane.berth@uni-graz.at

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6310-6609

“There is nowhere else quite like Managua,” stated the Nicaraguan magazine Envío in February 1989, lamenting the lack of a visible, symbolic place with which to identify the Nicaraguan capital. Managua was a really “odd” city, a “city without center,” a “third-world Los Angeles” with a few cars and shopping centers that looked like improvised market stalls (Equipo Envío 1989). Twentieth-century Managua raised concerns and curiosity among many observers because of its unique urban development. Since the 1972 earthquake, the city has been missing its historical center, which currently lives in the shadows of urban development. Nicaraguan intellectual Pablo Antonio Cuadra titled his essay on the city, “An Illness Called Managua”; others related to the city as “gringorized,” or the “inferno of the poor”1 (Rodgers 2012; La Prensa, June 8, 1973, 2; Téfel 1976).

The public debates between intellectuals, politicians, and the press over globalization and food consumption in Nicaragua have always focused primarily on the situation in the capital. Fast food, supermarkets, and mass advertising concentrated in Managua, leaving other regions of the country completely untouched. Both press coverage and intellectual critiques mainly relied on Managuan examples when discussing foreign influences on Nicaraguan consumption habits, which contributed to the Sandinista government’s negative perception of the city’s role in food supply after the 1979 revolution.

Managua’s place in the Nicaraguan food system was central, as all connections to the exterior ran through the capital. The Oriental Market, in particular, functioned as a distribution center for the whole country. Many producers from the surrounding villages sold their food at the market, thus the market had an urban and a rural base, which was one reason for its popularity (CIERA/UNRISD 1984, 42, 135-137, 152-154).

I will first briefly discuss the history of urban development in Managua prior to the Sandinista revolution in 1979. The revolution opened a chapter of urban change that affected housing, public spaces, shopping, and food consumption. It also led to a critical reevaluation of Managua’s place in the Nicaraguan food system. As the Sandinistas perceived consumption levels in the city to be too high, they considered Managua to be a burden on the self-sufficiency project and the state budget, as additional food had to be imported. In the last section, I explore changes in the distribution system and the rise of cheap fast food during economic and political transition between 1988 and 1993. The transition back to a capitalist market economy started with two adjustment programs in 1988 and was characterized by the abandonment of the Sandinista revolutionary food policy and intensifying social crisis.

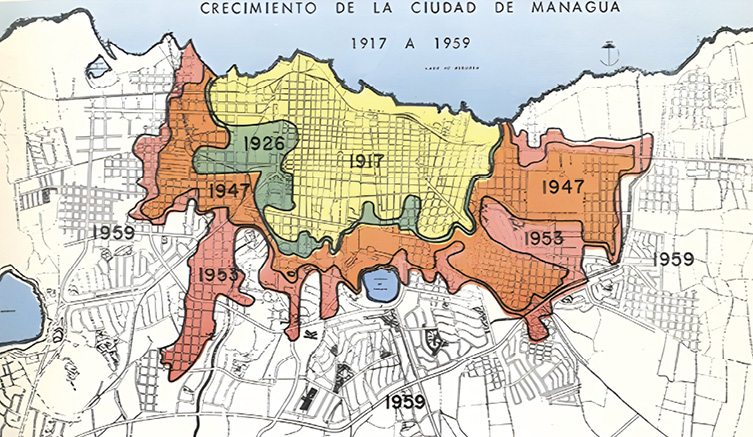

Managua was a latecomer in the ascent of Nicaraguan cities, but its rapid growth converted Nicaragua into the most urbanized Central American country of the 1960s. Managua, at that time a city with only about five thousand inhabitants, was granted capital status in 1852. During the 1930s, the city expanded to the west and east, attracting further immigration from the coffee-producing zones—mainly small farmers settling in improvised buildings at the margins of the capital (Sandner 1969, 80-91; Argüello Hüper 1986, 13-17).

From the 1950s, the Managuan population increased rapidly with the number of inhabitants doubling from 109,352 (1950) to 234,580 people (1963). The exodus from the countryside was a reaction to the expanding cotton industry. As small farmers were displaced to remote regions for basic grain production, many opted instead for a life in the capital. With accelerated urbanization, rural migrants from different parts of the country met, integrated more processed foods into their daily diets, and participated in the lively street food culture. Hence, urbanization also accelerated transcultural dynamics in food consumption (Polése 1998, 19). However, poor Managuans had only limited food choices.

Food prices began to rise in the early 1970s, which intensified social tensions in the capital. Students and workers mobilized against high food prices on the Managuan streets. Parallel to this, intellectuals raised concerns about the growing number of supermarkets, foreign processed food, and English-language advertisements. For example, Roger Quant Pallavicini criticized the “excessive absorption of gringo culture” in La Prensa newspaper. Sociologist Reinaldo Antonio Téfel denounced advertising as putting pressure on Nicaraguans to buy expensive products most could not afford (La Prensa, June 8, 1973, 2; Téfel 1976, 107). These voices contributed to the political resistance against dictatorship originating from students, the Sandinista guerilla FSLN (Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional) founded in 1961-1962, and sectors of the peasantry.

The 1972 earthquake increased social tensions over food in Managua. Shortly before Christmas, an earthquake destroyed over 90 percent of the buildings in the city center, including the central markets and the most important shops, restaurants, and government offices. As a consequence, food distribution problems affected the whole country. After the quake, the central area of Managua remained abandoned. Following the suggestions of US aid consultants, politicians and planners agreed on a decentralized urban development. But this took time to implement, and meanwhile, in everyday Managuan reality, large parts of the city were still destroyed and spontaneous settlements expanded along the lakeshores (Lee 2015; Agüello Hüper 1986, 23-26).

In the following years, the Somoza regime, which had been in power since 1936, reconstructed the city based on US models with suburbs and shopping centers. As a result, the city became more segregated with precarious living conditions for those in the popular districts, which affected food consumption in several ways. The poor districts lacked access to urban infrastructure, and bad water quality affected food quality and people’s health. Furthermore, the inhabitants had to travel long distances to the markets, relying on deficient urban transport. Finally, they needed to stock up on perishable products frequently as most families did not own refrigerators, which made them vulnerable to price abuses by the small local shops.

Throughout the 1970s, opposition to the dictatorship intensified and incorporated new groups, such as progressive Church representatives, entrepreneurs and conservative politicians. Also, the FSLN gained strength and challenged the regime through militant actions and participation in local revolts. President Anastasio Somoza Debayle became increasingly isolated on the international level and flew with his supporters to the US in July 1979. On July 19, the Sandinista revolutionaries took over the capital.

The Sandinista revolution aimed at transforming the country according to the “logic of the majority” and generated immense hope for social change. Sandinista food policy was based on four pillars: the aim of self-sufficiency, a state distribution system, price regulations, and food subsidies. Regarding consumption, the Sandinistas started political campaigns to encourage the use of local foods. Campaign strategists depicted the ideal revolutionary consumer as responsible and frugal. By contrast, the conspicuous enemy—the traditional consumer—was still attached to brand products and superfluous luxuries. Consequently, the Sandinistas substituted commercial advertisements with revolutionary posters, murals, and billboards in public places (Kunzle 1995, 64-65).

Sandinista discourse on commercial advertising and the effects of US culture was strongly influenced by theories of cultural imperialism. Nicaraguan intellectuals, social scientists, and activists had taken this approach since the 1960s, perceiving global capitalism as a threat to local culture. According to this vision, large foreign companies supported by local elites had created consumer desires through manipulative advertising (Tomilson 1991, 113-120; Mattelart 1986). In the 1980s, the Sandinistas denounced mass advertising as a harmful force spreading the consumption of imported goods in the country. Given the lack of foreign exchange, consumers should turn to national products. This call became more urgent when economic problems intensified.

Revolutionary food policy faced important challenges from the outset. First, the production of basic grains, milk, and meat did not expand fast enough to meet demand. Hence, food imports were still necessary. Second, US economic sanctions and the Contra war undermined Sandinista social reforms. Third, the continued migration to the cities and population growth represented another challenge for food policy and urban planning. Throughout the 1980s, Managua attracted rural migrants; between 1982 and 1984, fifty thousand Nicaraguans moved to the Nicaraguan capital every year. The total population increased from roughly 614,000 in 1980 to more than 754,000 in 1983 (Agüello Hüper 1986, 50).

With regard to food policy, the consumption levels in Managua in particular raised concerns among Sandinista politicians. Government functionaries referred to the elevated consumption rates as the “Managua problem.” Analyzing the strong trend toward urbanization in the country, Sandinista planners considered urban food supply as a key challenge for Nicaraguan food policy. According to a Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios de la Reforma Agraria (CIERA) report, Managua’s current place was a result of the development model promoted by the dictatorship; hence it constituted a barrier to revolutionary development. By characterizing Managua’s growth as hyper-urbanization, the authors clarified right from the start that they considered urbanization in Nicaragua to be exaggerated. In 1984, 30 percent of the Nicaraguan population lived in Managua (CIERA/UNRISD 1984, 1-5, 9-13).2 To challenge this trend, the Sandinistas promoted a redefinition of urban-rural relations. Instead of perceiving life in the cities as “superior,” Nicaraguans should value life in the countryside once again (Collins 1986, 176; CIERA/UNRISD 1984, 213-216). At the same time, however, another significant group of leading Sandinista politicians was portraying the Nicaraguan countryside as backward.

From the early 1980s on, Sandinista planners promoted urban gardening as a solution to overcoming supply problems and limiting consumerism. Urban gardens would improve the food supply and transform urban consumers into food producers. Food production in the city would move the rural world into the capital. In general, Managua was very well-suited for such an effort as most houses had a small patio or a backyard that allowed space for food production. Beginning in 1982, the government advocated for urban agriculture, employing militant propaganda. The Sandinistas promoted urban gardening as a countermeasure to “imperialist aggression” that would ensure the revolution’s survival (Barricada, June 18, 1985, 3).3 At the same time, the government organized social events, such as garden competitions and festivals. In an interview with this author in 2012, one woman, Rina Méndez Osorno, remembered enthusiastically her participation in a garden competition; her garden included 31 different varieties, among them oranges, papaya, green beans, and radishes.4 However, a 1982 survey documented resistance as well: out of 70 interviewees, only 35 people supported the project, while 25 opposed it and 10 expressed ambivalence. The opponents referred to problems with landholding rights, theft, and insufficient knowledge of gardening (CIERA 1983, 82-83).

Between 1982 and 1985, the supply situation in Nicaragua worsened considerably. The main reasons were the Contra war, economic sanctions, stagnating food production, and conflicts with the peasantry over agrarian reform. In addition, decreasing prices for Nicaraguan export products, large state investments and exchange-rate policy contributed to the economic crisis. By 1985, military expenditure amounted to 50 percent of the state budget, which left fewer resources for social reforms. In Managua, less basic food was available at subsidized prices; consumers complained about the lack of milk and meat. At the same time, prices on the black market soared. Finally, the Sandinista government changed its economic course, in 1985 introducing the first adjustment program including reduced social expenditures, tax increases, and a devaluation of the currency. Most food subsidies were eliminated, which strongly affected the urban poor (Barraclough et al. 1988, 57; Ricciardi 1991, 247-273).

As a response to increasing supply problems, the government reinforced the urban gardening campaign. In June 1985, it launched “Plan Managua.” At that time, the Nicaraguan Food Programme, PAN, estimated that there were 16 regional gardens, 608 institutional gardens, and 2,440 private gardens in the city (Barricada, June 24, 1985, 3). After the implementation of US economic sanctions, mainly international donors provided the seeds, as the Sandinista government lacked foreign currency. Overall, the contribution of urban gardens to the nation’s food supply is difficult to estimate. Food cultivation on home patios had traditionally been important for nutrition, especially in times of crisis. The campaigns as well as the provision of seeds might have motivated more people to participate. The gardens not only served as a personal supply but also provided the state distribution network with food (Barricada, June 18, 1985, 3; July 3, 1985, 3). On the one hand, gardens could not fill all gaps in supply as ongoing migration into the city reduced available spaces for cultivation. On the other, urban gardens contributed to more food diversity and higher calorie intake.

Sandinista food policy aimed at democratizing the food supply. In consequence, the revolutionary institutions changed the system of food distribution profoundly to make food more accessible for the bulk of the Nicaraguan population. Commercial supermarkets were transformed into popular supermarkets, pulperías— the small neighborhood stores— into popular stores, and new markets were founded to break the concentration on the Oriental Market. Even though the Sandinistas denounced it as remnant of the Somoza past, the market never lost its popularity and became a center of black market activities.

Sandinista narratives of Managuan markets painted everything black and white. The Oriental Market soon became a symbol of “one of the darkest legacies of the Somoza dictatorship,” characterized by chaos, misery, and the exploitation of the small vendors who had to pay rent for even the most basic stalls in the market (Barricada, June 23, 1980, 9).5 By contrast, state propaganda characterized the new markets as clean and neat spaces. In 1980, 11,000 vendors were selling their goods on the Oriental Market, some of them from distant parts of the country, some of them living in the market area. As a first step, the Sandinista government established mechanisms to improve conditions by closing bars, prohibiting prostitution, and establishing social projects. By contrast, advertisements portrayed the new markets as clean and safe offering fresh food in hygienic conditions6 (Barricada, April 18, 1980, 6; January 4, 1981, 1, 5). This narrative, however, does not tell the whole story; consumers continued to visit the Oriental Market throughout the revolutionary period, whereas the new markets faced serious difficulties in winning over clients (CIERA/UNRISD 1986, 155-159).

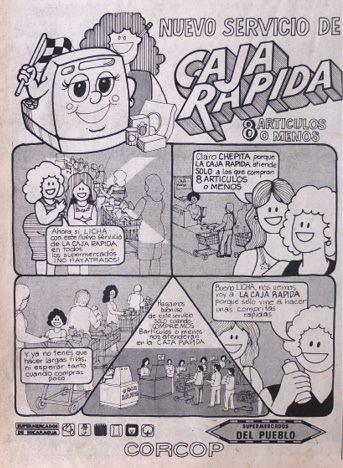

Although the Sandinistas failed to transform the Oriental Market completely, the revolution democratized access to Nicaraguan supermarkets. In the early 1980s, supermarkets opened their doors to a popular clientèle by offering basic products at fixed prices. At that time, two supermarket chains were operating in Managua: Supermercados de Nicaragua with 75 percent state ownership and CORCOP, which was 100 percent state-owned. Together, both chains served about 6-7 million customers a year, which demonstrates the democratization of access in the early 1980s (Barricada, February 2, 1980, 1, 9; May 5, 1982, 6). Barricada reported that supermarkets had gained a “popular feel” and stated: “Now they’re not the exclusive domain of four snobby nouveau riche ladies, but the place where ordinary people seek their food at lower prices” (Barricada, August 8, 1980, 1, 12).7 At the same time, supermarkets continued to offer products aimed at the middle classes, such as cosmetics, fruit juices, and sauces.

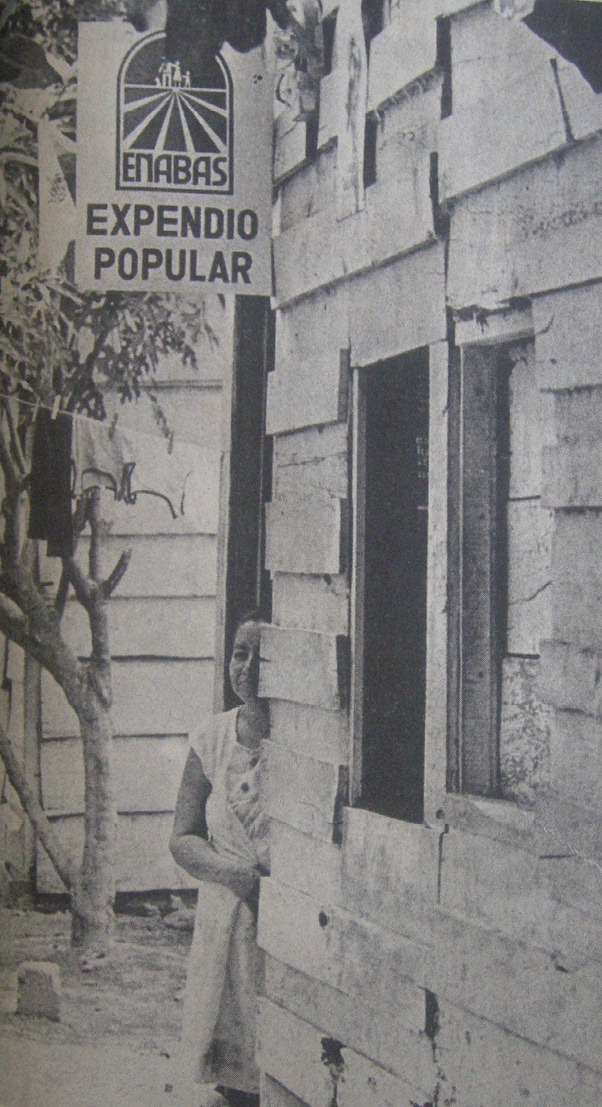

As the number of supermarkets in Managua was still limited, additional food sources at the district level were necessary. The government opened expendios populares to provide consumers with an alternative to pulperías. The number of expendios in Managua rose from 200 in 1980 to 983 in 1984 with each of them serving around one thousand people (Barricada, September 26, 1980, 7; August 10, 1980, 1, 12; August 8, 1984, 6; September 1, 1984, 1). For the poorest consumers, however, it was a problem that expendios only sold large quantities and did not offer credit (Collins 1986, 100-103; Utting 1989, 178). Hence, low-income consumers continued to shop at the markets and pulperías although food prices were sometimes higher. The difference between revolutionary propaganda and the reality of shopping at the supermarkets disappointed many consumers.

The deep supply crisis after 1984 affected all points of food distribution. The unavailability of many products and long lines characterized Managuan supermarkets, expendios, and pulperías. The discontent over the supply situation eroded the support for the revolutionary project. Sometimes, when people bought large amounts of subsidized food, such as milk or basic grains, the stores became so crowded that the police had to intervene, especially when conflicts over food distribution broke out Despite the overcrowding, revolutionary propaganda portrayed supermarkets as modern, efficient spaces accessible to all Nicaraguans. For example, one educational comic informed readers of the Sandinista newspaper Barricada of a fast lane in the supermarkets that allowed people with less than eight products to move on faster to the cashier (Barricada, May 5, 1982, 8).

While efficiency was portrayed as the ideal, daily realities challenged this vision of supermarkets. With increasing supply problems, long lines formed part of the daily shopping experience. State institutions divided workers into different categories and regulated their access to the official supply chain. This measure brought new crowds to the supermarkets. For example, in Bello Horizonte district, 250,000 customers arrived instead of the expected 70,000, which led to long lines, overworked cashiers, and a widespread sense of desperation (Barricada, July 3, 1985, 5).

Customers and supermarket staff accused each other of misconduct. While customers blamed supermarket employees for distributing scarce products to their own family members first, supermarket employees complained about people not accepting the need to wait in queues. Barricada frowned upon “uneducated” consumers reacting with aggression to the lack of products or consuming food in the supermarket without paying for it. In Bello Horizonte, on one day, people consumed 500 liters of milk within the supermarket. As a result, daily losses in one state supermarket peaked at 50,000 córdobas. Although supermarket workers demanded educational programs for consumers, the employees themselves contributed to problems by giving away products to relatives or increasing their personal quotas above the official limit (Barricada, June 18, 1985, 8; July 3, 1985, 5; June 11, 1986, 1; July 12, 1986, 1; March 12, 1987, 1; March 13, 1987, 3). While Barricada blamed individuals’ misconduct, people were also responding to the significant supply challenges of the mid-1980s. Despite the variety of shopping options available to urban consumers, basic products were often insufficient at most places.

The government reformed access to the supermarkets several times during the mid-1980s to avoid overcrowding. The Ministerio de Comercio Interior (MICOIN) also announced the construction of new supermarkets, which indicates that they played an important part in government supply strategies. The number of supermarkets in Nicaragua rose to 36 by 1987. However, supermarkets never became the dominant supply source. In the mid-1980s, 5,000 pulperias and 1,034 expendios existed in Managua that remained important for daily shopping in the poor districts (Utting 1992, 118; Barricada, March 4, 1985, 5). While the Sandinistas continuously criticized the import of US products, they never attacked supermarkets as a North American invention leading to automation, impersonal shopping, and standardization. Instead, for Sandinista planners supermarkets represented organized places, suitable as channels of “safe distribution,” which also reinforced their belief in modern technology as an organizing force. For Nicaraguan consumers, however, the supply situation became increasingly insecure and disorganized (Barricada, October 30, 1984, 12; May 28, 1986, 7). A “culture of shortage” (Chelcea 2002) had developed that made shopping a time-consuming, often frustrating experience. Speculation with scarce goods on the black market reached new heights.

From the perspective of the Sandinistas, the Oriental Market embodied the escalation of speculation within Nicaraguan society. In September 1984, the government estimated that 10 percent of Managua’s residents were working at the markets throughout the city. Struggling with their diminished buying power, citizens increasingly participated in this informal trade to earn a living (Kinzer 1991, 154). Not only chaos and speculation, however, made Sandinistas feel unhappy about the Nicaraguan market. The Oriental Market was also a focal point of political dissent as marketwomen soon resisted the government regulation of their operations, advocating for the autonomy to manage their business independently (González-Rivera 2002, 100-101). Consequently, vendors attacked Sandinista police and government inspectors on several occasions when they attempted to suppress speculation in the mid-1980s. Nonetheless, in September 1985, twenty thousand people sold their goods on the Oriental Market (Barricada, December 15, 1985, 3; September 30, 1984, 16; December 14, 1985, 5; September 2, 1985, 3). With skyrocketing food prices, public criticism of the supply situation intensified and gained presence even in the Sandinista newspaper.

The existence of an exclusive shopping opportunity for people with access to US dollars provoked a public controversy in the late 1980s. For the more affluent clientèle and foreigners, the Nicaraguan government created a special shopping space, the diplotiendas or dollar shops, probably designed according to the Cuban model (Collins et al. 1986, 42). The diplotiendas sold imported goods for foreign currency. In general, four groups frequented the dollar shops: foreigners living in Nicaragua; Nicaraguans with access to dollars; elites; and government officials (Collins 1986, 159). At the height of the economic crisis in 1987, public criticism of these exclusive shops emerged. Even Barricada posed very critical questions to Herty Lewites, such as “Is it proper that in Sandinista Nicaragua there’s a ‘diplotienda’ or international store in which products are sold in dollars? By allowing Nicaraguans with access to dollars to buy there, aren’t we stimulating more or less parasitic sectors of society, when in principle it’s only open to foreign diplomats and embassy staff?” (Barricada, February 20, 1987, 3).8

In the face of crisis and supply problems, many Nicaraguans could not understand why the government maintained a shop for luxury consumption. The longer the social crisis unfolded, the more people disapproved of the lifestyle of the Sandinista leaders (Lundgren 2000, 132). In late December 1987, the government had to declare a national food emergency, but the crisis intensified in 1988: in a situation of extraordinary hyperinflation, Hurricane Joan hit Nicaragua in October causing loss of cattle, seeds, and basic grains. The affected population on the Caribbean coast moved in part to Managua. This was the moment when it became clear that hunger had returned to revolutionary Nicaragua, even if political leaders did not dare to admit this in public. As a response to economic crises, the government installed two adjustment programs that strengthened market mechanisms in food distribution, abandoning the aims of the early revolutionary food policy. As a result of growing discontent and combat fatigue, the Sandinistas lost the 1990 election. The FSLN became an oppositional party, while the new government of the National Opposition Union (UNO) resumed economic relations with the United States and international financial institutions. In terms of consumption, the new political and economic elites promoted US consumer ideals and created new commercial establishments. Nevertheless, the years between 1988 and 1993 still represent continuity in the existence of a social crisis as well as the coexistence between state intervention and market intervention in the Nicaraguan economy.

During the economic and political transition, commercial influences resurged and even intensified after the 1990 election. New exclusive shopping facilities, however, coincided with widespread poverty. In the late 1980s, social crisis entered the supermarkets in spite of Sandinista efforts to improve workers’ access to basic supplies.

After the second adjustment package was implemented in June 1988, the social crisis became ever more visible. Market mechanisms gained strength in the state supermarkets, reversing the democratization process of the early 1980s. Apart from the availability of products, people worried about the high prices. As a result, robberies in Managua increased. For example, the Plaza España supermarket reported losses through product theft of about 20,000 córdobas in mid-1988. Robberies by women who hid their loot in their underwear received special attention. These women became known publicly as “gancheras” (Barricada, June 19, 1988, 2; May 31, 1988, 8). In July 1988, supermarket sales declined by 50 percent in one week. The supermarket chains introduced measures indicating that the model of the popular supermarket was about to change. Economic transition became visible in daily shopping spaces: first, supermarkets offered new services, such as bringing the merchandise to the client’s vehicle. Second, they increased publicity, for example by letting workers tempt customers into buying certain products with in-store demonstrations. Third, they promoted special offers (Barricada, August 3, 1988, 5; August 25, 1988, 3).

With liberalization and competition, commercial advertising once again expanded. With its structural adjustment, the government had reduced its financial contributions to some media; hence newspapers and radio stations depended on other income sources and increased advertising. The return to greater exclusivity and imported goods also indicated that the political project of democratic access to all supply channels had faded away.

During the transition between 1988 and 1993, market elements and state intervention coincided. However, the new Managua mayor after the 1990 election, Arnoldo Alemán, promoted a rapid urban transformation oriented towards the elimination of the revolutionary past and promoting the interests of the commercial sector.9 Alemán’s vision for urban change aimed at providing business opportunities to those former elites returning from exile in the United States. One of his prestige projects was the Shopping Center Metrocentro, relaunched in 1998.10 To wipe out the revolutionary past, the city’s government renamed public places and painted over most revolutionary murals (La Prensa, September 22, 1992, 3; Freeman 2010, 342). The return of exiled Nicaraguans from Miami also facilitated the distribution of US luxury goods in Managua. Some of them opened new stores in the recently founded shopping centers. To meet their demands, the government illegitimately authorized the use of foreign aid for luxury imports.

In the early 1990s, a paradoxical situation emerged: in spite of economic crisis and high poverty levels, fast food, supermarkets, and consumer culture became common throughout the capital. At the same time, the consumer appeared again as a figure in public debates. The newspapers Barricada and La Prensa reflected on these contradictory trends. Barricada coverage focused on high food prices and daily survival problems. While La Prensa did not deny the difficult economic situation, it introduced the new consumer environment in Managua to its readers. For example, it dedicated a special section to new consumer opportunities titled “The New in Managua” (La Prensa, October 8, 1991, 24).11

In 1991, the section featured a video rental store, a beauty products store, and a shop specializing in macrobiotic products. La Prensa depicted the new Nicaragua as a shopping paradise in some articles, and criticized wherever possible former Sandinista restrictions on free trade, despite the fact that even market advocates acknowledged that the growing social disparities were taking a toll on Nicaraguan society, allowing only a privileged few to participate in the new shopping world. In October 1991, La Prensa featured a political cartoon depicting a destitute woman with a headscarf, gazing longingly at a luxurious storefront display with a dummy wearing an elegant dress. As noted by a La Prensa journalist during a Metrocentro visit in December 1991, individuals typically ventured into these shopping centers solely to admire goods from afar, rather than making actual purchases (La Prensa, October 24, 1991, 4; December 17, 1991, 3).

The new commercial establishments, however, could only survive due to the reintroduction of credit in May 1991. Up until the beginning of economic liberalization, only cash payment was permitted, but in the late 1980s, for example, pulperías reintroduced credit. In 1992, the owner of a store for domestic appliances reported that workers frequently asked for credit because otherwise they could not afford their purchases (La Prensa, August 4, 1992, 4).

To attract customers during the economic crisis, the supermarkets modernized their installations and developed special offers for bulk-buying. With privatization starting in 1991, the supermarkets followed the trend of creating small shopping malls. The famous La Colonia chain was returned to the Mántica family in 1991. In April 1992, the government privatized four other former state supermarkets. These supermarkets announced in large advertisements the new variety of imported foods and won customers in 1991-1992 through offering the cheapest prices in Managua. By contrast, state supermarkets were soon abandoned. Because of the growing competition, all supermarkets tried to introduce new services to their customers, such as special sales of popcorn, soft drinks, and video rentals (La Prensa, August 3, 1990, 14; November 22, 1991, 1, 16; February 7, 1992, 1, 12; March 5, 1991, 1, 12; November 18, 1991, 1).

Evidence from consumer surveys shows that most Nicaraguans shopped in small neighborhood stores and at the Managuan markets for their daily supplies. However, people considered supermarkets as a good source for meat or fish as they tended to be more hygienic than other options. During the early 1990s, no consumer surveys were conducted in the Managuan supermarkets. Hence, this section uses findings from the late 1990s to reflect on changes in shopping behavior. A June 1997 survey conducted by a Nicaraguan consulting firm covered 460 interviewees, 92 percent of them housewives. The study found that only 30 percent of the interviewees shopped regularly in the Managuan supermarkets belonging to the younger, more affluent, and educated sector of Nicaraguan society. The other 70 percent mainly frequented the pulperías and the local markets. According to the survey, the main reason for shopping in the supermarket was the more hygienic storage conditions for food. Among the other services frequently used, the purchase of ice cream and fast food dominated. The majority of interviewees ranged across a middle-income group while higher and lower income groups were less represented (Corporación 1997).

This survey, supported by later Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos (INEC) studies, indicated a slow expansion of supermarket shopping around the year 2000. Calculations based on the INEC living standard surveys from 1998 and 2001 have demonstrated that even in Managua, only 10 percent of the population shopped in supermarkets while 40.8 percent frequented pulperías and 42.2 percent the markets. As the sample of respondents of the survey is broader, it provides more reliable data than the study conducted by a private consulting firm in 1997 (d’Haese et al. 2008, 610). The survey results show that the democratization of supermarkets was partially reversed in the 1990s. Faced with serious hygienic problems, however, consumers considered supermarkets a good source for meat and other more perishable foods.

Similar to the supermarkets, the situation of the pulperías remained ambivalent at the beginning of the 1990s. On the one hand, the reintroduction of credit created new opportunities. On the other hand, pulperías faced competition from street commerce and suffered from price instability. In light of the economic crisis, more customers needed short-term credit than pulpería owners provided, especially to people from the neighborhood. According to a survey conducted in the San Luis and Altagracia districts, between 55 percent and 66 percent of clients bought on credit. Credit was part of a “silent solidarity network” in popular districts as shop owners provided credit although they themselves struggled to make ends meet (Núñez 1996, 234-236; Geiser 1995, 95-96).

Pulperías competed with informal trade for customers during the period of economic crisis in the early 1990s. Opening a pulpería was one option to get by during the crisis. Contemporary calculations estimated that there were between 18,000 and 25,000 pulperías in Managua in the early 1990s. However, pulperos also struggled to acquire the merchandise for their shops, especially in the periods of extreme price volatility. Even worse, the crisis led to a flood of new street vendors who paid no taxes and thus, gained a small advantage in competition. As Barricada explained:

Managua’s going through a boom, not exactly of prosperity, but of the street vendors who have spread out everywhere in their thousands, like seeds scattered to the wind through every corner of Managua. They all share a common denominator: they’re born of crisis and necessity. It’s easy to find them. There’s no neighborhood, street, train platform, trail or bus stop, where you can’t find at least one (Barricada, October 21, 1990, 1).12

After the 1979 revolution, urban planning included workers and the urban poor for the first time in Nicaraguan history. The Sandinistas aimed at ensuring equal access to food through a new distribution system, price regulations, and food subsidies. In their vision, the ideal revolutionary consumer would reject imported food and value local alternatives. However, external challenges and internal contradictions weakened revolutionary food policy from the early 1980s onward. For example, access to supermarkets was successfully democratized, but the deficient supply situation produced increasing gaps between government propaganda and shopping reality. Contrary to their ideals, the Sandinistas themselves also created a privileged shopping world, the dollar shops, where a segment of government employees shopped regularly.

Given the serious supply problems, the Sandinista government perceived rapid urbanization and the concentration of trade networks in Managua as a problem. To reduce high levels of urban food consumption, the government started a militant urban gardening campaign: urban consumers should reconvert into food producers and contribute to the success of the revolution. However, the revolutionary effort to promote the countryside was a failure as rural-to-urban migration continued throughout the 1980s. Nevertheless, urban gardening strengthened rural elements within the city, especially in the urban outskirts. The contribution of urban gardening to daily nutrition is difficult to assess; but the particular urban structure of Managua with its large empty spaces proved helpful for an urban transformation where housing and agriculture could co-exist.

Nevertheless, the supply situation worsened continuously from the mid-1980s on. Managuans relied increasingly on food aid or developed other survival strategies, such as maintaining relations to the countryside or informal exchange of food. Despite a large variety of tactics, people suffered from hunger during the transition years. With the structural adjustment in the late 1980s, the transition entered shopping spaces. While popular education campaigns lost importance, commercial propaganda and imported products were revived. Hence, market forces gained strength again and undermined the democratization of the supply system.

After the 1990 election, the new Managuan mayor, Arnoldo Alemán, and returning elites vigorously promoted US models for urban development and consumer culture, bringing the old solutions from the Somoza period back to the forefront. The national government supported investments in a new consumer world with exclusive shops and commercial centers. Hence, the visions of a “gringorized” city reappeared on the scene. For many Nicaraguans, however, the only way to participate even in a limited way was credit. Nonetheless, large sectors could only access this world by looking in shop windows. The situation in the early 1990s remained contradictory. On the one hand, supermarkets attracted customers with cheap prices. On the other hand, surveys indicate that most people frequented markets and pulperías for their daily shopping. Managua’s center never regained its place as a commercial and social heart of the city, a loss that continues to shape the special urban development of Managua to the present day.

Argüello Hüper, Alejandro. 1986. La ciudad de Managua: Historia y desarrollo hasta 1979. (Objektbezogene Stadtplanung im Forschungsschwerpunkt, Arbeitsfeld Planen und Bauen in Entwicklungsländern, 21). Hamburg: Technische Universität Hamburg-Harburg.

Barraclough, Solon L., Ariane van Buren, Alicia Garriazzo, Anjali Sunderam and Peter Utting. 1988. Aid That Counts: The Western Contribution to Development and Survival in Nicaragua. Amsterdam: Transnational Institute.

Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios de la Reforma Agraria (CIERA), ed. 1983. Distribución y consumo popular de alimentos en Managua. Colección Cmdte. Germán Pomares Ordóñez. Managua: Centro de Investigación y Estudios de la Reforma Agraria.

Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios de La Reforma Agraria (CIERA)/United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD). 1984. Managua es Nicaragua: el impacto de la capital en el sistema alimentario nacional. Managua: Centro de Investigación y Estudios de la Reforma Agraria.

Chelcea, Liviu. 2002. “The Culture of Shortage during State Socialism: Consumption Practices in a Romanian Village in the 1980s.” Cultural Studies 16 (1): 16-43.

Collins, Joseph D. 1986. Nicaragua: Was hat sich durch die Revolution verändert? Agrarreform und Ernährung im neuen Nicaragua. With the assistance of Frances Moore Lappé, Nick Allen, and Paul Rice. S.l.: Nahua.

Collins, Joseph D., Michael Scott and Medea Benjamin. 1986. No Free Lunch. Food and Revolution in Cuba Today. New York: Grove Press.

Coorporación. 1997. Corporación Más X Menos Supermercados La Unión: CUAS Supermercados Managua, Nicaragua. Managua.

d’Haese, Marijke, Marrit Van den Berg and Stijn Speelman. 2008. “A Country-Wide Study of Consumer Choice for an Emerging Supermarket Sector: A Case Study of Nicaragua.” Development Policy Review 26 (5): 603-615.

Equipo Envío. 1989. “There is Nowhere Else Quite Like Managua.” Revista Envío 91: n. p. http://www.envio.org.ni/articulo/2767.

Freeman, James. 2010. “From the Little Tree, Half a Block toward the Lake: Popular Geography and Symbolic Discontent in Post-Sandinista Nicaragua.” Antipode 42 (2): 336-373.

Geiser, Sepp. 1995. “‘Ni del uno ni del otro . . . soy de mi familia’: Eine ethnologische Untersuchung zu Alltag und Politik in einem Unterschichtquartier von Managua/Nicaragua.” Licentiate Thesis, University of Zürich.

González-Rivera, Victoria. 2011. Before the Revolution: Women’s Rights and Right-Wing Politics in Nicaragua, 1821-1979. Pennsylvania State University Press.

Kinzer, Stephen. 1991. Blood of Brothers: Life and War in Nicaragua. Putnam.

Kunzle, David, ed. 1995. The Murals of Revolutionary Nicaragua, 1979-1992. University of California Press.

Lee, David J. 2015. “De-Centring Managua: Post-Earthquake Reconstruction and Revolution in Nicaragua.” Urban History 42 (4): 663-685.

Lundgren, Inger. 2000. Lost Visions and New Uncertainties: Sandinista profesionales in Northern Nicaragua. University of Stockholm.

Mattelart, Armand, ed. 1986. Communicating in Popular Nicaragua. International General.

Núñez, Juan C. 1996. De la ciudad al barrio: Redes y tejidos urbanos: Guatemala, El Salvador y Nicaragua. Universidad Rafael Landívar.

Polèse, Mario. 1998. “Ciudades y empleos en Centroamérica.” In Economía y desarrollo urbano en Centroamérica, edited by Mario Lungo and Mario Polèse. Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales.

Ricciardi, Joseph. 1991. “Economic Policy.” In Revolution and Counterrevolution in Nicaragua, edited by Thomas W. Walker. Westview Press.

Rodgers, Dennis. 2012. “An Illness Called Managua: ‘Extraordinary’ Urbanization and ‘Mal-Development’ in Nicaragua.” In Urban Theory beyond the West: A World of Cities, edited by Tim Edensor and Mark Jayne. Routledge.

Sandner, Gerhard. 1969. Die Hauptstädte Zentralamerikas: Wachstumsprobleme, Gestaltwandel und Sozialgefüge. Quelle & Meyer.

Téfel, Reinaldo A. 1976. El infierno de los pobres: Diagnóstico sociológico de los barrios marginales de Managua. El Pez y la Serpiente.

Tomlinson, John. 1991. Cultural Imperialism: A Critical Introduction. London: Pinter.

Utting, Peter. 1989. “La oferta interna y la escasez de alimentos.” In La economía política de la Nicaragua revolucionaria, edited by Rose Spalding. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Utting, Peter. 1992. “The Political Economy of Food Pricing and Marketing Reforms in Nicaragua, 1984-87.” The European Journal of Development Research 4 (2): 107-131.

Manuscript received: 08.05.2024

Revised manuscript: 29.11.2024

Manuscript accepted: 19.12.2024

1 The word gringorización derives from the term gringo used in Latin American Spanish to refer to foreigners from the United States.

2 The Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios de la Reforma Agraria (CIERA) formed part of the Ministry of Agriculture and conducted research on the government’s food policy.

3 Translation from Spanish original.

4 I have changed the name of the interviewee to maintain her privacy.

5 Translation from Spanish original.

6 Despacho conjunto sobre abastecimiento. 1984. Instituto de Historia de Nicaragua y Centroamérica (IHNCA) Archives, Managua. Sesión, no. 2 (June 12). EB 025 D 33.g2.

7 Author’s translation from Spanish original.

8 Translation from Spanish original.

9 Arnoldo Alemán Lacayo (born 1946) is a Nicaraguan lawyer and politician. From 1990 to 1995, he served as mayor of Managua and won the 1996 presidential election against Daniel Ortega.

10 The shopping center is owned by the Salvadoran enterprise Grupo Robles that constructed the first center in 1974. In the 1990s, the firm invested in its expansion and reopened it in 1998.

11 Author’s translation from Spanish original.

12 Author’s translation from Spanish original.