DOI: 10.18441/ibam.25.2025.88.101-117

Andrés Dapuez

CONICET, Argentina

andres.dapuez@uner.edu.ar

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0253-9619

The austere Lycurgus erected a statue to laughter, calling it the gift of the gods (Bakhtin 1984, 70).

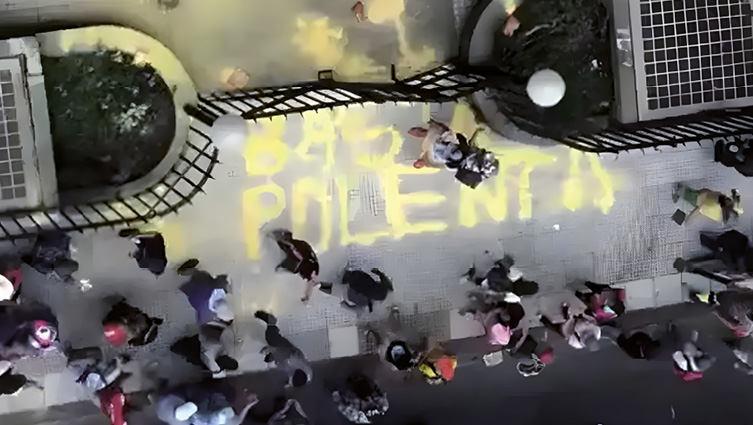

In a demonstration on October 28, 2021, activists of the Teresa Rodriguez Movement (TRM) wrote on the sidewalk of the Argentine Ministry of Social Development “Basta de Polenta,” meaning, among many other things, that they were fed up with state transfers of that grain. Throughout the morning, protesters blocked traffic in downtown Buenos Aires and other cities. The demonstrators, usually known in Argentina’s media under the general name of picketers or social organizations (Piqueteros or Organizaciones Sociales), were complaining against multinational corporations but also against the government’s social policies. The former were officially blamed for inflation in food prices, the latter for the insufficient transfer of resources to social organizations. However, they were also expressing their anger and frustration against internal and antagonistic sectors of the El Frente de Todos (“Everyone’s Front”) government that was in charge of administering state transfers in cash and in kind.

At 12:30 p.m., the TRM’s scheduled meeting with the Minister of Social Development, Juan Zavaleta, was anticipated an hour early by activists who broke into the ministry building and destroyed computers, some furniture in the building lobby and busts of Perón and Evita were thrown off their pedestals and onto the floor. Television news programs broadcast aerial footage taken from the upper floors of the Ministry building. The haunting images of the legend “basta de polenta” written on the floor with the eponymous grain were reproduced in TV shows, social media, and WhatsApp messages.

Polenta has become a metonym for poor people’s food. During Argentina’s long economic crisis, and at least since 2011, it has come to epitomize not only state transfers of staple food, but also an official “moral economy” of subsistence (Thompson 1971, 1991; Scott 1976; Fassin 2009), driven by what I tentatively call the “providential state.” By 2021, polenta transfers began to be seen as a replacement for cash transfers, or even worse, as a token indicating the devaluation of those who received it. Too-cheap polenta was contrasted with too-expensive red meat. In the election campaign, Alberto Fernández and Cristina Fernández promised the restoration of the weekly practice of barbecuing and the enjoyment of pleasurable feasts. Instead of such popular aesthetics, the people were moralized in the aftermath of the Covid-19 crisis. The debates about cash transfers valuation (DuBois 2023) radicalized when this staple food of the poor was transferred for no purpose. Viewed in the long-term as a form of “repugnant consumption” (Roth 2007, 41), polenta, and its jokes, imposed constraints on a politically moralizing state. The government that proposed alimentary charity, against a backdrop of real and imaginary food riots, may also have been corroded by humor, breaking what Pablo Semán called the progressive consensus (2023) and its “moral economy”. This leads to the following research question: at what turning point does the concept of moral economy become useless for explaining consumer preferences based on tastes or to explain how moral economies change from one to another on the basis of non-ethical or amoral phenomena? And consequently, what role does political laughter play in making taste a non-moral decision maker?

In my research conducted in 2020 and 2021, I utilized WhatsApp and Zoom interviews to gather data from distinct groups: beneficiaries of state transfers and representatives of the Confederación de Trabajadores de la Economía Popular (CTEP), Movimiento de los trabajadores excluidos (MTE). Additionally, I engaged with representatives from the national, provincial, and municipal levels of government. In addition, I conducted interviews with provincial and municipal government officials, including the Secretary of Social Development of the City of Paraná and other local authorities. My findings suggest that the consumption of laughter, and more specifically, polenta jokes, may have facilitated a shift in the moral economy from a progressive to a right-wing orientation.

My research revealed that food transfers (as opposed to cash transfers) to the poor were used as an urgent state intervention to address official concerns about potential looting. All of my interviewees, state officials at different levels, asserted that it was not only challenging to procure food for distribution during the initial months of the covid-19 lockdown, but that these transfers were regarded as indispensable to avert social unrest. At a time when “there was no food to distribute,” several leaders of different social organizations, the Paraná municipal government, state officials from the Entre Ríos provincial government, and the national government, feared that the silence and uncertainty about the dates for the delivery of basic foodstuffs could lead to social unrest. When this opacity was partially overcome and food transfers reached all distribution channels, in the last months of 2020 and in 2021, the state’s handouts began to be considered as superfluous. State provision changed the meaning of these handouts from a highly desired and requested intervention to one that devalued the recipients themselves.

In this paper I start depicting the political moralization of food and hunger of the Alberto Fernández’ government. Then, I describe how a typical sense of economic crisis was changed by the context of pandemics, analyzing how moral and economics were joint and disjoined by the later crisis and by polenta jokes. I conclude by saying that although the jokes about polenta hurt those who received these food transfers, it would seem that they also helped redirect aid recipients to another moral economy, especially by reiterating that promises of red meat consumption were made deceitfully.

Didier Fassin traced the concept of “moral economy” back, through many authors and uses, to E.P. Thompson’s book (1963) The Making of the English Working Class. Fassin notes that the concept of the moral economy “appears incidentally when Thompson evokes the looting of shops and sheds during the period of rising bread prices (Fassin 2009, 1239). In a footnote, however and despite the later importance of the concept, Fassin points out that neither “moral economy” nor “moral” appears in the book index. The “older moral economy of the peasants” (Thompson 1963, 68) acts as a cultural reason for the industrial workers to behave in an extreme manner, as if it were an ancient well-known limit that has been placed on the economy. Importantly, it was thus not hunger directly, but an old and embedded cultural trait that drove the peasants to loot the shops and barns; making a moral claim about injustice involves a “plebeian culture” and not only rioting mobs (Thompson 1974). An ancient moral culture seems to have been awakened by the debasement of money, activating a primordial cultural subjectivity. In this example, as in many others, looting and rebellion may be triggered by a monetary crisis, in this case inflation, rather than directly by physical hunger. As money dissolves through inflation, or at least loses its ability to mediate between things, an ancient moral consciousness awakens to fill a cultural void, a problem of representation related to lowering of the value of currency.1

In many uses of the compound “moral economy” the moral element acts to short-circuit the economy through “culture.” At the same time as it constrains the economy, morality seems to gain autonomy by animating a larger cultural framework. Culture, as a set of values, in this idealized understanding, maintains its own autonomy based on the emerging moral values of an ancestral peasantry, inherited by the working class. These, at least two temporalities at work in the compound of “moral economy” keep the concept somehow “clumpish” (Hann 2018, 231; Thompson 1991) in order to work. Perhaps if Thompson’s term has been so successful, it is because it works as an ambiguous phrase that can be understood in multiple ways. Nonetheless, for Fassin, the moral-economic amphibology can be rescued from its inherent ambiguity; he even pluralizes it, speaking of the multiple moral economies of a social compound.

According to Fassin, Thompson’s moral economy has two components, the moral (norms, values and obligations) and the economic (encompassing production, distribution and consumption). How, then, are morality and the economy connected? Which term encompasses, subsumes and limits the other? Although it can be argued that it is sometimes necessary to moralize the economy, to find its ethical limits of subsistence, beyond which life is not worth living, the opposite can also happen: the economization of ethics and morals can sometimes be seen as an essential mechanism. If unjustified hunger or the lack of stable food consumption leads to a rupture of the moral contract, which in its turn brings the whole economy into crisis, then too much moralizing can also be bad for the economy and for life as a whole. At some point, disorganizing social control and throwing away polenta may have gone beyond any kind of morality and instead made a bold economic statement.

In the following I will describe how the Argentine moralizing state and its provision of free food to the poor (also to moralize them) have been discursively constructed after many years of food programs. Humor and joking relationships are well known subjects for anthropological inquiry (Apte 1985; Oring 1992; Beeman 1999; Bricker 1973; Douglas 1968; Limon 1989; Radcliffe-Brown 1940; Mauss 2013 [1926]) but little has been said about their moral relationship with the economy.

The Argentine Program Against Hunger (Programa Argentino contra el Hambre, PACH), was announced on the same day that President Alberto Fernández took office (December 10, 2019). It indirectly referred to another food program called the National Food Program (Programa Alimentario Nacional, PAN) from 1984. Mimicking President Raúl Alfonsín’s (1983-1989) diagnosis of an economic emergency—at that time caused by the military dictatorship—Alberto Fernández’ justification for the PACH was initially based on a critique of the economic crisis triggered by the peso devaluation of the former president, Mauricio Macri, in 2018. Meanwhile the PAN program discursively constructed access to food as a “constitutional right” by guaranteeing “certain minimum social rights,” and was intended to be transformed into an instrument “to forge a new social pact” for the long term (Adair 2020, 46-55). The PACH used the same rhetoric but for the shorter term of the Fernández presidency (2019-2023).

While PACH made references to PAN, Argentinian commensality, and poverty, “hunger”—depicted as an urgent condition to be addressed immediately—was its protagonist. The “Table against Hunger” or Mesa contra el Hambre first met on November 15, 2019. Then, almost one month before taking office, newly-elected presided Alberto Fernández brought together well-known Argentinian social leaders, politicians, and celebrities to discuss the implementation of policies for the most vulnerable (Infobae 2019). The Mesa contra el Hambre met only five times and was disbanded on November 6, 2022, after 18 months without any meetings taking place (Klipphan 2022).

Despite Argentina’s well-developed system of cash transfers to combat food poverty, Mesa contra el Hambre and the new political meaning of the concept of ‘hunger’ created a new function for the state: the provision of food on a massive scale. A much more complicated social welfare system was introduced to promote government-friendly intermediaries in charge of distributing food and setting up new networks of cronyism.

Launched on December 18, 2019 with the delivery of 7000 “Alimentar” cards (to buy food) in Concordia, Entre Ríos—at that time the city with the worst poverty indices in Argentina—the PACH aimed to do more than make food a tool to deal with the very short-term crisis produced by the government of Mauricio Macri. It promised a better and more pleasant future for Argentina’s lower classes. At the time, and according to the official discourse, the PACH aimed to create a new moral contract among Argentines. In this sense, the program was designed to establish a state-sponsored commensality for the poor.

The concept may have been used to moralize the “neoliberal economy” inherited from President Mauricio Macri. In Argentina, a middle-income country that produces food and feeds more than ten times its own population, hunger was not a pervasive social issue comparable to obesity and malnutrition. Notwithstanding the exhortatory impact of the PACH and its Mesa contra el Hambre, Argentina exhibited merely “low levels” of stunting and hunger, as evidenced by the Global Hunger Index (GHI 2023), which assigned a score of 6.4 for the period spanning 2018 to 2022. Nonetheless, in the last year of Alberto Fernández’s presidency (2023), six in ten children were considered to be poor and obesity rates were also on the rise, probably due to the massive consumption of low-quality diets, rich in fat, carbohydrates and sugar in combination with a lack of physical activity. However, Argentina remained one of the countries with the “highest consumption of red meat in the world” (around 53 kg per capita for the 2023, according to a report by the Rosario Stock Exchange, Bloomberg 2023).2

Widespread polenta rejection among popular consumers, then, was not only fueled by this food’s redundant omnipresence. A well-remembered TV political advertisement was among one of the many references to barbecues in the 2019 presidential campaign of Alberto Fernández. During the campaign, a TV spot promised a glorious “return” to the typical Argentine tradition of the asados on weekends (Clarín 2019). Blaming Mauricio Macri, the incumbent president, not only for the partial loss of the asado tradition, the decrease of red meat consumption, and the enjoyable commensality of the Argentines, the advertisement became a political promise of consumption for the years of the Fernández administration (Clarín 2019; see also Teubner in this dossier on chicken and Fernando Enrrique Cardoso’s promise of consumption). However, the unfulfilled promise of the return of asado to the “Argentine table,” after the 2020 Covid crisis and the economic crises that followed, became the subject of jokes.

At the same time as red meat consumption declined in the Fernández period (2019-2023), largely due to the devaluation of the national currency and the consequent increase in meat exports, polenta appeared in the popular imagination as its uncanny double. In 2021, social networks such as Reddit, Telegram, and WhatsApp, as well as the mass media, were flooded with messages mocking the free polenta handouts as an unreliable and cheap substitute for the promised meat. The opposition mocked Frente de Todos voters with various images of polenta.

In Argentina, during the “ASPO” Covid-related lockdown of the 2020s (a Spanish acronym for Obligatory and Preventive Social Isolation), the state, but also government-friendly social movements and social organizations delivered food to the poor. Meanwhile, a more precarious but flexible and adaptable new statehood reinforced from below the former state logic of distribution. Under this new logic of the state at the time of the lockdown, resource transfers (in cash and in kind) were aimed at immobilizing large vulnerable sectors of impoverished people in neighborhoods, settlements, or areas. By restricting their mobility to a given “territory” (the word used by political leaders to refer to what is outside of the state remit), ASPO’s ghettoization required enormous logistics that sometimes failed, creating more insecurity among the supposed beneficiaries. Confined to a defined “territory,” the beneficiaries of the state allowance could move freely within the area, but were forbidden access to the main city and commercial centers. Not only did goods circulate from commercial warehouses to distribution centers, which were sometimes owned by government-allied organizations and sometimes state-owned, to be transformed into free food for the disadvantaged sectors, but the government and its allied organizations reminded the beneficiaries and society at large that politics ruled the economy. However, this process of large-scale de-commodification of staple foods was reliant on massive food purchases or donations from food banks. In some cases, and in order to speed up the distribution of the goods, prices above the market price were paid.

News of overpriced purchases of edible oil, pasta, sugar, lentils, and rice by the National Ministry of Social Development not only stopped the purchases, but also paralyzed the ministry’s deliveries to the provinces for almost a month and a half, in which period the moral panic about looting grew. The complaint filed by the Office of the Attorney General for Administrative Investigations states that the contracts were awarded to “a small group of companies” that “mostly offered prices higher than those certified by the Comptroller General of the Nation.” Finally, more than a year later, Federal Judge Sebastián Casanello ruled that no crime had been committed and dismissed Daniel Arroyo, then Minister of Social Development, and 17 others (Telam 2021). First the temporary lack of food transfers, then the news of overpriced food and finally the restrictions on going to the center to buy food, may have highlighted the superiority of the market as a place of provision over the state’s redundant practices.

One of my interviewees, an important leader of the Entre Ríos construction union and secretary of the General Labor Confederation of that province, corrected me in an interview when I suggested that a crisis could also be interpreted as an opportunity to change behavioral patterns and economic structures. Covid-19 seemed to have succeeded in transforming the routine crises of Argentines (Muir 2021) into a more acute one: “We go from crisis to crisis... in crisis... in crisis... and [the idea that crises are opportunities] may look good in books, but not when those crises are actually happening” (Secretary of the provincial CGT, interview on April 16, 2021).

This response, like that of other sources, highlights the growing climate of urgency. By exaggerating the dangers of hunger, the government created a political culture that could have led to a major crisis. Until food circulation normalized in the last months of 2020, this vital danger was perceived as twofold. The poor could spread the virus, but also destabilize the government. In this respect, social organizations acted as a buffer to prevent contagion and destabilization. They had to improvise soup kitchens, but also raffles to raise funds when they lacked resources. In the first months of the blockade, they began to look for alternative sources of food and ways of organizing themselves in the poor neighborhoods to face the new emergency. Later, the consumption of the free food offered by the state, directly or indirectly, did not only confirm the humble status of the recipients of the poor-quality food. It aimed to “fix” in the “territory” populations that could become dangerous to the upper classes to which the state functionaries belonged, while reassuring the rest of society that there would be no looting and no popular uprisings. Much later, when the extra food became superfluous, the consumption of polenta jokes was not only a relief from the fear of death and political turmoil. It was also a break from the strict moralization imposed on the poor by the state and its allied social organizations.

During the Covid-19 lockdown, schools and soup kitchens offered free meals, promoting a state-sponsored “charity” that was widely criticized not only by the opposition but also by pro-government allies. Once it became impossible to go downtown to buy food after the initial period of shortages, the state-run food distribution system itself became a significant problem. In the most vulnerable neighborhoods, educational institutions assumed the role of free food distribution centers, while classrooms were closed, and no classes were held. Subsequently, in June, the school kitchens ceased operations, resulting in a significant alteration to the way food was distributed to the most economically disadvantaged students. As a consequence of the transition from the provision of hot meals for vulnerable children on site to the distribution of food parcels for family consumption, there was an increase in demand for food. In this context, while some government beneficiaries sold surplus food to raise cash, others simply gave it away to family members. The amount of food was also changed. In the primary school I surveyed, the number of food portions initially increased from 50-60 per day to 200 per day. This change occurred when the canteen was closed for on-site consumption and plastic containers were distributed outside the school. In July 2020, the delivery of processed food in these containers was discontinued. Delivery of dry food in plastic bags began. In July 2020, each of the packages was to consist of one kilo of rice, one 500 g packet of noodles, one box of tomato paste, one 900 cc bottle of oil, and one 500 g packet of noodles per student. After the first month, in August, a tin of corn, a tin of peas, and a tin of lentils were added. Snacks were also part of the package, and the following items were also in the bag: a 900 g packet of powdered milk, a 400 g jar of jam, a 180 g packet of cocoa, a packet of crackers, a box of dry dessert, and one kilo of sugar.

The food delivered did not only change in terms of what was provided. It went from being hot and shared on the table between pupils and teachers, to being served cold and uncooked in a container for transport to the family table. In this state, the food, which was supposed to be prepared by the parents, could also be exchanged for cash. According to one headmaster (and other interviewees), surplus food was sold at very low prices. This bottom-up monetization was criticized by school teachers, middle-class neighbors, and even pro-government street-level bureaucrats. Criticizing both the erratic state and the commodification of food by the poor, these neighbors noted that the educational goal of the schools was being compromised. They feared that children were being fed worse than before the closure, when they ate at school. The moral imperative of educating citizens was, according to these narratives, abandoned by both parents and the state (national, provincial, and municipal). Food had become an end in itself, rather than a means to the educational process of the children involved. Stories of parents who converted surplus food into cash and a vote-buying state that gave away food indiscriminately converged at one point.

From June to December 2020, the number of food packages distributed in Paraná schools increased, mainly due to demand. In 2021, two kilos of seasonal fruit and three kilos of vegetables (carrots, potatoes, and onions) were added to the popular “bolsón.” In the school where I conducted my research, all 370 pupils received bolsones or “food bags.” Since its introduction during lockdown, the food bag has become a privileged political instrument. Its origin (in this case provincial, but there were also those of municipal origin or delivered by social organizations whose origin was national) has, however, on numerous occasions, given rise to strong disputes about capitalizing on the gratitude and recognition of the beneficiaries towards those who distributed them. Polenta was not mentioned as part of the bolsón, perhaps it was distributed in abundance to the poor by national, provincial, and municipal governments and private food banks. According to my informants, polenta was the most commercialized commodity received by the poor, who sold it with other surplus food for getting cash.

In early May 2020, in the popular online magazine for social science students Amphibia, Ariel Wilkis, a sociologist and dean of the San Martin University in Buenos Aires, predicted the emergence of a “new moral economy” as a typical aftermath of the Argentine crises. Wilkis’s call for a new moral economy was not unique. State officials made similar normative demands to repair the effects of a tightly enforced state lockdown during the pandemic. Wilkis highlighted the link between the amount of cash in circulation and morality (see also Wilkis 2017, 2020; Valverde 1994). After the “disappearance of cash,” as happens in all “great crises” in Argentina, the remaking of the economy would depend on a new “moral economy” to rebuild Argentina from “ruins” (Wilkis 2020). As in other uses of the term “moral economy,” the assumption that these two terms can be conjoined unproblematically was not made explicit. Although Wilkis had always praised the moral links between money and its particular uses in social evaluations, the anti-economic rhetoric of the Frente de Todos emphasized that a moral state-directed aid for the poor would benefit them as compensation for the 2020-2021 economic crisis. As if “moral” economies were only “those organized around reciprocal exchange because social obligations to bind people to each other and support the needs of communities” (Browne 2009, 11), this state-sponsored “morality” was intended to subordinate the other component element of the compound (economy).

In this sense, on March 23, 2020, President Alberto Fernandez stated categorically: “Many people told me that I was going to destroy the economy with the quarantine. If the dilemma is the economy or life, I choose life. Afterwards we will see how to organize the economy” (Perfil 2020). Free food distribution relied on deeply rooted practices among the Argentines (in the family, school, church, and the military) and the fear of looting, or at least an immoral hunger as its trigger, seem to have been conjured in part by these practices. At least in government discourse, food was considered a much more moral medium than cash. In this sense, the government disregarded Wilkis’ warning about the perils of a radical reduction of circulating money endangering society’s moral standing. In the lockdown context, cash was issued to around 9 million people though an extraordinary cash transfer called Emergency Family Income (Ingreso Familiar de Emergencia, IFE), in conjunction with other measures.3 This was delivered in just three instalments of $10,000 Argentinian dollars (around US$50) each, in May, July, and September 2020. In the same period, tons of food were distributed by the Ministry of Development. In March 2020, the PACH was supposedly to be supplemented with direct food transfers. Polenta later inundated the homes of the poor. The unpredictable pandemic provoked a series of predictable state responses against the moral panic about looting and governmental destabilization (see Adair in this dossier).

To return to the argument of the paper, in order to reduce the mobility of the population in the Covid-19 health crisis, the Frente de Todos government intended to secure and transfer food to the supposedly unstable popular slums and neighborhoods (the middle and upper classes were to be confined to their homes and not to districts). These distributions of free food to the poor reactivated a series of historical repertoires of the economic crises of 2001, 1989, and earlier. Updating fears of “social uprising,” “looting,” and former Argentine food riots, the redundant responses of political leaders to a supposedly imminent crisis were ridiculed. As well as ridiculing the government for its moral use of the poor, the rejection of polenta and the jokes made about it also indicated some limits to the moralization of the economy. At the same time as the state was made absurd by the jokes and the polenta surpluses, the concept of a “moral economy” ceased to function in the usual way.

Laughter erupted in 2021 when the perception of “something mechanical encrusted on something living” (Bergson 1950, 29) was made patent by images of polenta taking the form of ribs, chorizo, and other red meat pieces from Argentinean barbecues (see figure 2). In this case, the mechanics of morality constraining the living economy became apparent. Failed promises of asado circulated and were consumed as the Covid-19 health crisis became a new economic crisis. President Alberto Fernández also turned into a ridiculous “puppet” or “Capitán Polenta.”4 On the other hand, avoiding lootings by state food transfers was, at last, a partially achieved objective.5 The state’s repertoire of “free” deliveries of food and cash reached a turning point when humor, good or bad, about state handouts mocked the waste of state resources. As Hann has argued in relation to Hungarian peasants, a pro-market moral economy (Hann 2010) seems to have prevailed among Argentina’s poor just before the 2023 elections, when the ultra pro-market Javier Milei won. In the Argentinean case, laughter may have been an important tool in bringing about this change.

According to Mary Douglas, although she praised Bergson’s (1889) discoveries about humor, she found that there was a moral limit to his analysis.

Bergson’s reduction is “inadequate” firstly because it introduces a new moral judgement into the analysis of jokes. For Bergson the joke is always a chastisement: something “bad,” mechanical, rigid, encrusted is attacked by something “good,” spontaneous, instinctive. I am not convinced either that there is any moral judgement, nor that if there is one, it always works in this direction. Second, Bergson includes too much. It is not always humorous to recognise “something encrusted on something living”: it is more usually sinister, as the whole trend of Bergson’s philosophy asserts. Bergson’s approach to humour does not allow for punning nor for the more complex forms of wit in which two forms of life are confronted without judgement being passed on either (Douglas 1968, 263).

Similarly, Bakhtin criticizes Bergson by pointing out that, beyond good and evil, “certain essential aspects of the world are accessible only to laughter” (Bakhtin 1984, 66). Beeman also restates that humor makes people think in a novel way despite its offensiveness. Humor and offensiveness are not mutually exclusive. An audience “may be affected by the paradox as revealed in the denouement of the humor despite their ethical or moral objections and laugh in spite of themselves (perhaps with some feelings of shame)” (Beeman 1999, 104).

In Argentina, a ridiculous instance may have existed before the subsequent right-wing moral transformation. Erupting at a moment when some people recognized the tensions and limits of the government’s attempts to use free food distribution to impose a certain redundant morality, this instance may have disjoined the government morality from the “economy”. The joke “seen as an attack on control” (Douglas 1968, 364) was rather a revenge of the economy (psychic or otherwise) against the progressive morality. In a process that was also humiliating for the poor, a new site for a pro-market economism opened up as a more vibrant arena for participation. In this sense, it was not only the rich and the right-wing opponents of the Fernández government who ridiculed the empty promise to restore red meat as a popular food. The people who voted for and supported the Fernández government were also mocking it and themselves through polenta jokes, in a way that could be described as changing “cognitive frames” through the use of humor (Beeman 1997).6

Deeply intertwined with the Argentinians’ sense of who they are, the ideas and practices of food consumption were used to moralize about poverty, to express frustration at the Covid-19 lockdown, and then to objectify a desire for political change, to react against previous moralities, and to embrace, later, an economy with a brand-new morality. Changing the cognitive frame of food consumption through the use of humor may have been crucial to the political transformation that took place in Argentina in the 2023 elections. If Javier Milei’s practically reversed every element of the former moralizing state, from left to right, this happened because most of the Argentinean people who voted for him underwent a cognitive change through humor.

The election campaign of Alberto and Cristina Fernández made a promise to their poorest voters: they would improve their purchasing power so that they could eat asado again. As Mintz made clear in the introduction to his book Tasting Food, Tasting Freedom, “[f]or many people, eating particular foods serves not only as fulfilling experience, but also a liberating one -an added way of making some kind of declaration” (1996, 13). Clearly, the experience of eating asado in Argentina has these characteristics of liberating and celebratory consumption. However, the free distribution of polenta during the economic crisis that followed the COVID-19 health crisis negatively sanctioned these expectations. Instead of being able to go to the market and buy meat themselves, those who believed in this electoral promise received donations of cheap food. These transfers could have been seen as devaluing the recipients. Through a series of jokes that circulated mainly on WhatsApp, the unfulfilled promise was transformed into laughter, and laughter into political sanction. At the same time as the government moralised the crisis and the economy, the consumers of the polenta jokes laughed at the moral economy proposed. In the process, the main figures of the government themselves were made ridiculous.

Left-wing demonstrators first challenged the government’s determined portrayal of poverty and free handouts as moral phenomena par excellence through a message in polenta letters (“b-a-s-t-a-d-e-p-o-l-e-n-t-a”). As food for thought, these images provoked a reframing of moral consumption. The cornmeal, now transformed into letters, provoked a series of new consumptions of jokes. Through the media, many people consumed the polenta’s political message of “enough is enough,” as if the images transmitted were of a festive event to make polenta repugnant. On the other hand, disgust and fun were recombined in another way. For an emerging pro-market and right-wing electorate, the polenta symbolized and condemned not only state charity, but its recipients and the state itself. By ridiculing the government’s use of “hunger,” a growing right-wing audience in turn humorously critiqued the government’s failed red meat consumption pledges. More interestingly, the polenta rejection helped to challenge moralizing definitions of poverty that trap the poor in representations of themselves. An image of the conveniently polenta-eating poor, created at the will of the state, was torn apart, first by anger and later by humor.

State aid, designed to act in successive and routine crises, ended up implying not only an anti-neoliberal repertoire (Muir 2021, 5), but also an anti-economic and moralizing one, in which “aid” ultimately constrained the movement of people to the marketplace. The state’s constant accusation of the market as amoral or immoral, or the typical assumption that “the economy tends to be without morals, knowing only the law of supply and demand and leaving all values except monetary values in the dust” (Maurer 2009, 263), was challenged with humor. This too-moral economy gave rise to jokes and feelings of repugnance at the superfluous consumption of polenta. For some people, the disgusting consumption of polenta turned the state into a repugnant institution in itself, especially when the political promises of better consumption were frustrated by recurrent food crises and their moral prospects. The providential state and its free food transfers with a social agenda (to avoid looting) had resorted to the symbolic use of hunger and poverty in order to produce a “suffering subject” (Robbins 2013); but this was overcome, among other instruments, by polenta jokes. In this sense, jokes about looting and the associated moral panic may have been used to reframe (desired) food consumption and hunger with a new, revealing distance and to propose new (in this case right-wing) moral economies.

In response to the Fernández government’s failed promises of consumption, laughter seems to have helped to open up a passage between the elementary components of the moral with the economy. Polenta jokes not only allowed an inverse moralization. The good moral and bad economy did not only change valences. The encompassment of the moral over the economics was questioned and for a while disjoined. Despite the fact that the polenta jokes were meant to hurt polenta consumers, they also seemed to make them laugh and to radically reorient themselves politically. The moral dichotomization (good/bad) have been short-circuited by humor and aesthetics, at least for a brief moment, producing an unpredictable new reorientation in an uncertain world.

Adair, Jennifer. 2020. In Search of the Lost Decade: Everyday Rights in Post-Dictatorship Argentina. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Aiassa, María J. 2024. “Lote de Noticias: Ganadería y finanzas.” ROSGAN: Bolsa de Comercio de Rosario, 18 de Marzo.

Apte, Mahadev 1985. Humor and Laughter. An Anthropological Approach. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. 1984. Rabelais and His World. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Beeman, William O. 1999. “Humor.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 9 (1/2): 103-106.

Bloomberg (Redacción Bloomberg Línea, Argentina). 2023. “Cuánta carne se consume en Argentina y la comparación con el resto del mundo.” https://www.bloomberglinea.com/latinoamerica/argentina/carne-en-argentina-cuanto-se-consume-y-comparacion-con-el-mundo/.

Bricker, Victoria. 1973. Ritual Humor in Highland Chiapas. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Browne, Katherine E. 2009. “Economics and Morality: Introduction.” In Economics and Morality. Anthropological Approaches, edited by Katherine E. Browne and B. Lynne Milgram. Plymouth: AltaMira Press.

Carrier, James G. 2018. “Moral Economy: What’s in a Name?” Anthropological Theory 18 (1): 18-35.

Clarín 2019. “El video de campaña del Frente de Todos con la promesa de asado.” https://www.clarin.com/politica/video-campana-frente-promesa-asado_3_9ms16y5by.html.

Douglas, Mary 1968. “The Social Control of Cognition: Some Factors in Joke Perception. Man.” New Series 3 (3): 361-376.

DuBois, Lindsay. 2023. “Valuing and Devaluing: Struggles over Social Payments, Dignity, and Sneakers.” Economic Anthropology 10 (2): 233-245. https://doi.org/10.1002/sea2.12282

Fassin, Didier. 2009. “Les économies morales revisitées.” Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales 64 (6): 1237-1266.

GHI. 2023. https://www.globalhungerindex.org/argentina.html.

Gudeman, Stephen. 2016. Anthropology and Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Infobae. 2019. “Quiénes estuvieron junto a Alberto Fernández en el Consejo contra el Hambre.” Infobae, November 15. https://www.infobae.com/politica/2019/11/15/quienes-estuvieron-junto-a-alberto-fernandez-en-el-consejo-contra-el-hambre/.

Klipphan, Andrés. 2022. “Se disolvió la Mesa contra el Hambre, la gran apuesta del Gobierno que naufragó en medio de la escalada inflacionaria.” Infobae. November 22. https://www.infobae.com/politica/2022/11/06/se-disolvio-la-mesa-contra-el-hambre-la-gran-apuesta-del-gobierno-que-naufrago-en-medio-de-la-escalada-inflacionaria/.

La Nación. 2023. “Con el salario hoy se compran casi 10 kilos menos de asado que el promedio de los últimos 10 años.” June 2. https://www.lanacion.com.ar/economia/campo/con-el-salario-hoy-se-compran-casi-10-kilos-menos-de-asado-que-el-promedio-de-los-ultimos-10-anos-nid02062023/.

Limon, Jose. 1989. “Carne, Carnales, and the Carnivalesque: Bakhtinian Batos, Disorder and Narrative Discourses.” American Ethnologist 16 (1): 471-486.

Mauss, Marcell. 2013 [1926]. “Joking Relations.” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 3 (2): 317-334.

Mintz, Sidney. 1996. Tasting Food, Tasting Freedom: Excursions into Eating, Culture, and the Past. Boston: Beacon Press.

Noticias. 2021. “‘Capitán Polenta’, el muñeco de Alberto Fernández que venden en Mercado Libre.” May 10. https://noticias.perfil.com/noticias/informacion-general/por-el-bajo-consumo-de-carne-en-mercadolibre-venden-un-muneco-de-alberto-capitan-polenta.phtml

Oring, Elliott. 1992. Jokes and Their Relations. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky.

Radcliffe-Brown, Alfred. 1940. “On Joking Relationships.” Journal of the International African Institute 13(3): 195-210.

Robbins, Jael. 2013. “Beyond the Suffering Subject: Toward an Anthropology of the Good.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 19 (3): 447-462. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.12044.

Roth, Alvin E. 2007. “Repugnance as a Constraint on Markets.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 21 (3): 37-58.

Semán, Pablo. 2023. Está entre Nosotros. ¿De dónde sale y hasta dónde puede llegar la extrema derecha que no vimos venir? Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI.

Serres, Michel. 1982. Hermes: Literature, Science, Philosophy. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Scott, James C. 1976. The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebellion and Subsistence in Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Thompson, Edward P. 1968 [1963]. The Making of the English Working Class. New York: Penguin Books.

Thompson, Edward P. 1971. “The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century.” Past & Present 50: 76-136. http://www.jstor.org/stable/650244.

Thompson, Edward P. 1974. Patrician society, plebeian culture. Journal of Social History 7 (4): 382-405. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh/7.4.382.

Thompson, Edward P. 1991. Customs in Common: Studies in Traditional Popular Culture. New York: New Press.

Valverde, Mariana. 1994. “Moral Capital.” Canadian Journal of Law and Society 9 (1): 213-232.

Wilkis, Ariel. 2017. The Moral Power of Money. Morality and Economy in the life of the poor. Redwood City: Stanford University Press.

Wilkis, Ariel. 2020. “Coronavirus y distancias sociales. Una nueva economía moral”. Anfibia, May 20. https://www.revistaanfibia.com/una-nueva-economia-moral/.

Manuscript received: 08.05.2024

Revised manuscript: 29.11.2024

Manuscript accepted: 06.01.2025

1 Fassin makes clear that unobservable moral economies are deduced from observable phenomena after the facts, such as lootings and revolts: “In his 1971 article, E.P. Thompson develops the concept of moral economy, not in relation to the workers, but to the peasants, and not to explain class consciousness, but to interpret food riots. And it is from now on that the British historian criticizes the interpretation of popular uprisings as quasi-mechanical consequences of increases in the purchase price of food or decreases in the sale price of grain. Contrary to the widespread idea that we are dealing with “rebellions of the stomach” - what he calls a “spasmodic vision” of revolts - there is, according to him, no economic determinism, and even less a physiological one, of protests and mobilizations” (Fassin 2009, 1247).

2 In 2017 the average red meat consumption was 57.5 kg, falling steady to 47.9 kg in 2021, the year of the above-mentioned protest (2018: 56.7 kg; 2019: 51.3 kg; 2020: 50.5 kg; 47.9 kg in 2021, and recovering to 49 kg per person in 2022; Aiassa 2024).

3 Some of these measures included reinforcements in family allowances and social plans, such as: i) the payment of an extraordinary bonus for the Universal Child Allowance and the Pregnancy Allowance for Social Protection equivalent to a monthly amount, ii) the payment of an extraordinary bonus to retirees who receive only one retirement pension, and iii) the postponement of the payment of instalments for loans from the National Administration of Social Security (ANSES) for the months of April and March.

4 Reddit, “Capitan Polenta.” Accessed April 1, 2024. https://www.reddit.com/r/argentina/comments/n9yiar/capit%C3%A1n_polenta_el_mu%C3%B1eco_de_alberto_fern%C3%A1ndez/

https://www.reddit.com/r/argentina/comments/ivoxig/capit%C3%A1n_polenta/

https://www.reddit.com/r/argentina/comments/mbglww/polenta_fern%C3%A1ndez/.

5 Some lootings took place after a 22 percent devaluation of the Argentine peso in August 2023. Immediately afterwards, prices of commodities, especially food, hiked around 30 percent. https://www.france24.com/es/minuto-a-minuto/20230824-cuatro-claves-para-entender-los-saqueos-en-argentina and https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/argentina-scattered-looting-portends-ugly-election-race-inflation-bites-2023-08-23/.

6 Beeman sustains that “[t]he basis for most humor is the setting up of a surprise or series of surprises for an audience. The most common kind of surprise has since the eighteenth century been described under the general rubric of “incongruity.”… revealing one or more additional cognitive frames which audience members are shown as possible contextualizations or reframings of the original content material (Beeman 1999, 105). Also, on the basis of Freudian theory and its reworking by Berger (1999), José Emilio Burucúa distinguishes 3 different types of laughter (arising in his study from images): a carnivalesque one springing from the social practices of the inversion of roles; a satirical and critical laughter, and, a humorous laughter that, by means of the absurd or irony, spares us long and painful processes of learning about the reality of the world (Burucúa 2001 and 2007).